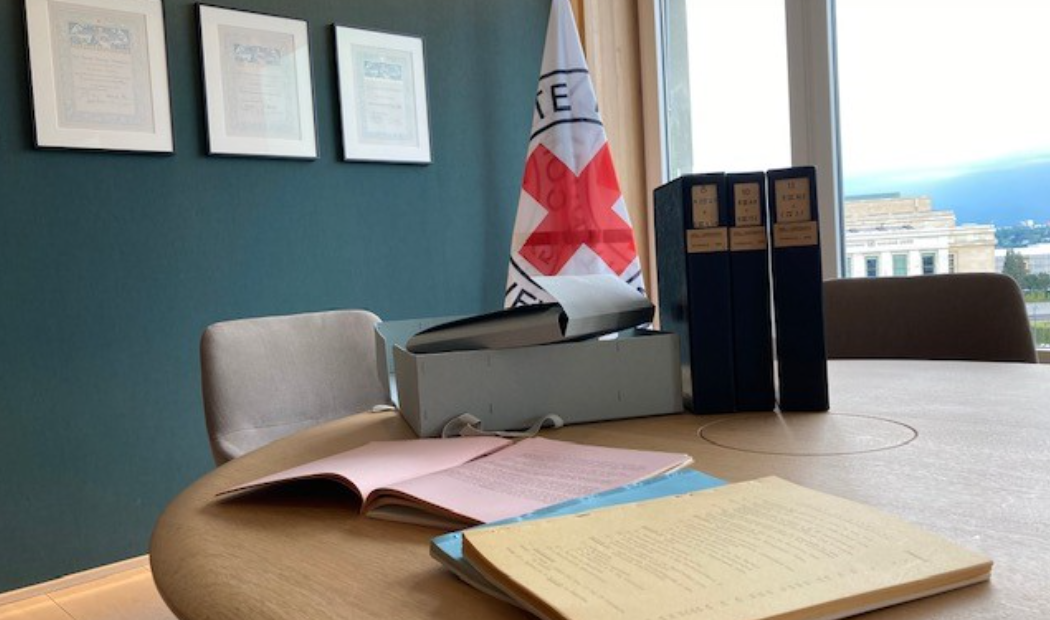

This collection contains information on prisoners and global detention issues, along with the painstaking details of families searching for missing members through the notes and letters of countless soldiers, nurses, volunteers, diplomats and delegates.

Since its inception, the ICRC has endeavored to preserve and record its global humanitarian action as well as the history of international humanitarian law (IHL).

Today these archives attest the rich and unique legacy of modern humanitarian action and the continuing – and growing – relevance of IHL.

Continuously updated, the ICRC archives are a resource with global value, so a new and ambitious digitalization initiative is seeking to make it globally accessible.

“It’s not about files, documents, and data, it’s about people and their connection to the past,” says Brigitte Troyon Borgeaud, the ICRC’s Head of Archives and Information Management Division.

“These archives don’t just belong to the ICRC but also to the people we assist and protect, so they should have direct access,” she says. “This is about bringing the story back to the people.”

Accessible Archives

Troyon Borgeaud and Digitalization Project Head, Michèle Hou, are tasked with the important job of making the archives accessible.

And the scale of the ICRC archives is simply staggering: there are more than 100 million pages containing crucial information on millions of victims of conflict.

Every year around 135,000 people visit the archives online and in person, while several hundred thousand more use the archives’ audiovisual website regularly to access photographs, videos and audio files.

The foundational documents of the ICRC are found in the archives so it’s fitting that they reside in the basements of the Geneva headquarters as well as the ground floor of the logistics center in Satigny.

The archives contain the history of the ICRC, but they also help people to connect, trace lost relatives or meaningful individuals and uncover the fate of loved-ones.

A set of five million prisoner of war records from World War I have already been digitized and made publicly searchable, but this is just a small percentage of ICRC’s complete archives.

The task of making digital versions of handwritten record—and indexing them together without duplications—is almost impossibly daunting for a single archivist with a scanner.

But artificial intelligence, machine learning and crowdsourcing promise a faster solution to the problem of providing public access to these records.

Of Prisoners & Families

The World War II prisoner archives—supplied by the detaining States and including such details as name, date and place of birth and detention, and date of death, transfer or repatriation—contain 36 million records.

Of these, roughly six million cards relate to French prisoners of war (PoWs), who are the most searched for by the public. It is estimated that these records, once reconciled, will represent up to three million individuals held in captivity during the conflict.

It is these individuals whose stories will become easily accessible for the first time through this initial digitalization project. And the ICRC hopes much more will follow.

The file cards containing details of prisoners who may have died or disappeared means the archive is “sometimes the only remaining proof of the existence of these people,” adds Troyon Borgeaud.

Such archives contain “a legacy of humanity in its darkest ages, because it shows the suffering of people in wars,” says Troyon Borgeaud. “The truths contained in the records may be traumatic, but they must be known.”

For now, access to the archives is limited by their physical form, meaning it is necessary to visit Geneva in person, or take advantage of the limited times the Second World War archives are opened up to remote requests for information.

And demand is incredibly strong. Public queries are only offered three times a year due to staffing constraints but during those periods the ICRC archivists “are simply overwhelmed with requests from families,” says Troyon Borgeaud.

“We recognized that this method of operating was not sustainable, not acceptable,” says Troyon Borgeaud. “It’s hard for families and it’s hard for our staff.”

For the World

Digitalization is the solution, says Hou. “We want to try to use machine learning technology to avoid manual indexing,” which is incredibly time-consuming.

With support from ICRC’s Innovation Facilitation Team, Hou is testing the effectiveness of machine learning technology for reading handwritten records with the intention of quickly sorting and organizing the data so it can be searched in multiple ways – by name, date, prison location and so on.

“The technology for handwritten text recognition (HTR) already exists and is quite effective, especially at recognizing old types of handwriting,” says Hou, because it has been honed on other heritage archives.

There is a precedent in the ongoing digitalization and indexing of archives, such as the League of Nations and the Arolsen Archives of civilian victims of Nazi persecution. These archives combine HTR with human verification to open up searchable information to the public, a system the ICRC hopes to emulate should the initial pilot prove successful.

But Troyon Borgeaud emphasizes that the technology is a means to an end. “Behind all this machine learning, it’s about the people,” she says. “There are so many touching, sad and uplifting stories in the archives. They should not remain beyond reach.”