The blog post by Shadeen Ali is based on the longer article Ottoman Laws of War by the same author which forms Chapter 4 of Laws of Yesterday’s War 3.

The Ottoman Empire was a vast and powerful state that ruled over Europe, Asia, and Africa. As the longest reigning Islamic empire, the Ottomans formed a bridge between the East to the West for six centuries. The success of the Ottoman empire can be attributed to both its political power and military might. From the reign of Sultan Mehmed II (r. 1451 – 1481) to the early 18th century, Ottoman policy and practice incorporated both Islamic law (shari’a) and Sultanic law (kanun) in a relatively consistent manner. The concept of justice is a central tenet of Islamic governance. Professor Wael Hallaq states that the shari’a is the axis of governance, pointing the way to justice. However, justice cannot be achieved without political authority, which in turn cannot exist without a powerful military. I claim that the Ottoman conceptualisation of ‘justice’ was deeply rooted in Islamic traditions which regulates the conduct of hostilities.

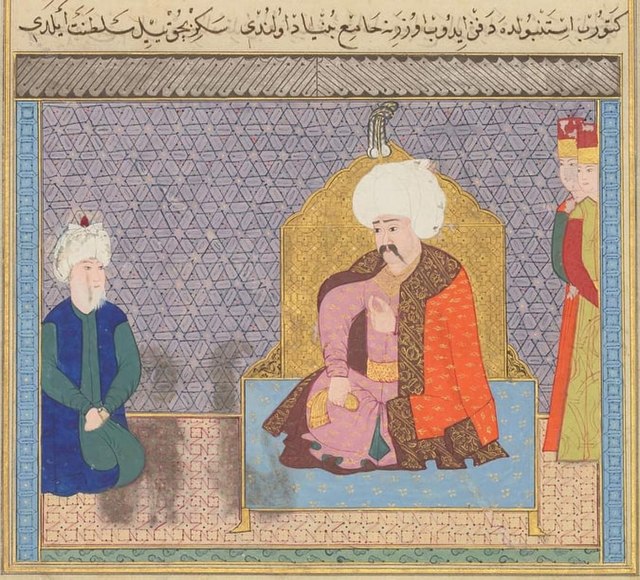

The Circle of Justice

To understand Ottoman history, one must look closely to its guiding principle of imperial governance: the ‘Circle of Justice’ (daire-i adalet). This was a concept of justice that emphasised the interdependence between rulers and subjects and formed the basis for Ottoman security and protection. First portrayed in Aristotle’s Secretum Secretorum (The Secret of Secrets) for Alexander the Great on how to rule, it was later reproduced by Arab scholars Ibn al-Biṭrīq (d. 815 CE) and Ibn Khaldun (d. 1406 CE). By the 15th century, the concept of the Circle appeared in works written or translated in Anatolia, forming the criteria for the Sultan’s governance. The Ottoman adaptation of the schema appears in ethical philosophical treatise, Ahlâk-ı Alâî, of Kınalızâde Ali Çelebi (d. 1572 CE):

There can be no royal authority without the military

There can be no military without wealth

The subjects produce the wealth

Justice preserves the subjects’ loyalty to the sovereign

Justice requires harmony in the world

The world is a garden, its walls are the state

The Holy Law (shari’a) orders the state

There is no support for the shari’a except through royal authority

The underlying philosophy of the Circle was to obtain security most effectively through nizam (harmonious order). The Ottoman’s imperial concept of ‘world order’ (nizam-ı ‘âlem) delegated the fundamental duty of ensuring and maintaining justice and order within the empire to the sultan as the royal authority, a duty entrusted by God (cenab-ı Allahın vediası).

Sovereignty: The Responsibility of Rulership

Political life in the 15th century Post-Mongol Islamic world was dominated by steppe traditions of governance and a universalist ideology. Given that the region comprised of four empires, the Timurid, Safavid, Shaybanid, and Ottoman, political hegemony could have been accomplished by any of the regional Muslim rulers. What distinguished the Ottomans from the other hereditary sovereigns was not their lineage, or lack thereof, but rather their success at establishing sovereignty by force.

Ottoman scholar, Mustafâ Âlî (d. 1660 CE), states that the highest form of kingship is bestowed upon a world-conqueror who establishes a universal domain. This universal sovereignty cannot be refuted as its success was God’s will and evidence of His favour. This highest form of kingship was achieved by Sultan Mehmed II through his conquest of Constantinople. Mehmed II’s absolute authority and political-military power was demonstrated through his titles: Gazi, Khan, and Caesar. As Khan, Mehmed II prevented any of Timür’s descendants from claiming overlordship. Likewise, as Caesar, Mehmed II seized possession of the Roman imperial throne, caused the downfall of Byzantium, and prevented an anticipated crusade. The ideal of ‘world-conqueror’ was then further established by Sultan Selim I (r.1512 – 1520) through his conquest of the Mamluk Sultanate. Selim I assumed the title of Amir ul-Mu’minin given to the Caliph of the Muslim state and Khādim al-Ḥaramayn aš-Šarīfayn “Protector of the two holy cities” (Mecca and Medina), fortifying the empire’s religious legitimacy.

The responsibility of rulership was held by the Ottoman sultan as zill Allah “God’s shadow on earth” and bestows the sultan with the power to dispense justice. Âlî notes that this divine sanction of rule was acquired and, importantly, maintained through diligent observance and protection of the shari’a.

The Ottomans institutionalised this concept of justice in the administration of both shari’a and kanun. The Qur’an instructs those given ‘authority on the land’ to “judge between people with justice and do not follow desire, lest it lead you astray from the path of God.” The concept of a universal justice, as specified in the shari’a, was practiced under customary usage (örf), and embodied in kanun. The reconciliation of which was achieved under Kanuni Suleyman I, the Lawgiver (r. 1520 – 1566). Kinalizade suggested that the measure of harmony and the religious, social, and administrative perfection reached during the reign of Sultan Suleyman I was comparable to Plato’s ideal model of a ‘virtuous city.’

Military: Justice and Jihad

Power could not persist without the internal dynamics of a political system, which could not persist through military force alone. Ottoman sultans understood that the success and prosperity of the empire depended on the cyclical relationship between politics, military, and the people. The Ottomans adopted the ideology of jihad and assumed the role of military leaders of the holy war against infidels. As “God’s shadow on earth,” it was the utmost duty of the sultan to maintain social order and harmony, and to protect his empire from external threat.

There were distinct rules governing the Laws of Armed Conflict and harsh penalties for those who violated these laws. The principles and requirements for a just war were commonly held to be: just cause, a legitimate authority, righteous intention, and an invitation to Islam. The Islamic jus ad bellum is defence against aggression which justified defending against attacks by dar al-harb (abode of war). Offensive war had also been prevalent due to the perpetual state of war common during the early-modern period. Territorial conflicts and the relentless raiding activity between the Ottomans and their neighbouring European states was justified through the objective of both expanding and protecting the domains of the Islamic empire, which constitute just causes for war.

Professor John F. Guilmartin Jr. discusses religion as a casual mechanism in Ottoman wars but mentions the importance of understanding the total economic, social, and cultural context to explain the underlying intention, stating that ‘the roots of war lie deep within the social fabric’. He summarises Ottoman wars as falling into the following categories:

- War against Christian states to expand and protect dar al-Islam

- War against Shi’i states to protect the integrity of the territories

- War against rival Sunni states

- War against internal rebellion and rival dynasties

Though these categories of Ottoman war differed in regard to opponent, they are alike in terms of objective and intent – ‘world order’ (nizam-ı ‘âlem).

As mentioned above, the Ottoman’s believed that the ruler reigns through divine right, justified and legitimised within an Islamic framework. The belief of divine right to rule is contingent on the acceptance by the people. Just rule would support a powerful army and ensure the secure and unchallenged rule of the sovereign. The sultan as the legitimate authority must rule justly to preserve his subjects’ loyalty and gain that of those newly conquered.

Lastly, to be considered lawful, hostilities by a Muslim army must be preceded by an invitation to Islam to mitigate unnecessary suffering. The requirement for an invitation and the of offering peace is based on the Qur’anic instructions that: “If the enemy is inclined towards peace, make peace with them.” Gaza’a nature as offensive warfare requires that the inhabitants of a city, both combatants and non-combatants, are firstly invited to adopt Islam. If they reject this offer, then another offer will be made granting protection and citizenship to those that surrender in return for the payment of poll tax (jizyah) to the Ottoman state. If both invitations are refused, hostilities become justified.

The conduct of Ottoman armies was based on the Qur’anic directive to “fight in the cause of God against those who fight you, but do not exceed limits.” Considered to be the Islamic jus in bello, this verse guides Muslim armies to conduct warfare according to the shari’a and the sayings and practices of the Prophet Muhammad during battle. Ottoman conduct towards conquered peoples during and after wars was comparatively tolerant. Dhimmi status would be provided to the non-Muslim populations, granting them protection, self-governance, and the ability to maintain their own cultural traditions and practices. This system to manage the population based on tolerance was crucial to encouraging loyalty. In exchange for their autonomy, the people would pay a poll tax. This tax would underwrite the army, which ensured the long-term stability of the empire. Maintaining order, ensuring justice, and coming full circle.

However, this tax system was not the only one imposed on Ottoman subjects. The devşirme system was a form of human levy imposed on Christian Balkan families which involved the controversial practice of enslavement during armed conflict. The practice was controversial for its unlawfulness as it was prohibited under Islamic law to enslave those with protected dhimmi status. The forcible recruitment of Christian boys into the janissary corps was unequivocally prohibited and inherently unjust. While it played a crucial role in the strengthening of the Ottoman army, the coercive nature of this conscription led to uprisings and the weakening of the Ottoman social structure. While it was an effective means to an end, the devşirme system could not exist alongside the shari’a and ‘justice’– it was as impractical as an attempt to square the circle.

Each element of the Circle of Justice depended on the others for its success. The basis for this Circle can be found in the essential role played by the shari’a which links all the elements back to one another. The Ottoman’s waged wars to uphold justice, to which they would be successful so long as they remain just. Unless they upheld this cyclical commitment to justice and social order, they would succumb to the cyclical process of decline and overthrow. The fragility of this socio-political concept is observed in the absence of an element. The absence and violation of Islamic laws during armed conflict allowed injustices to spread throughout the Ottoman empire. To employ the devşirme system is to disobey the shari’a; to disobey the shari’a is to break the circle. The Ottomans demonstrated that one simply cannot cut corners in the Circle of Justice.

*

Shadeen Ali is a graduate of the Adelaide Law School and was a research associate at the Research Unit on Military Law and Ethics.