What is the ICRC ’s position on terrorism?

The ICRC strongly condemns acts of violence that are indiscriminate and spread terror among the civilian population. It has done so on many occasions.

IHL does not provide a definition of ‘terrorism’, but prohibits most acts committed in armed conflict that would commonly be considered ‘terrorist’.

It is a basic principle of IHL that persons fighting in armed conflict must, at all times, distinguish between civilians and combatants and between civilian objects and military objectives. This principle of ‘distinction’ is the cornerstone of IHL. Many IHL rules specifically aimed at protecting civilians – such as the prohibition against deliberate or direct attacks against civilians and civilian objects, the prohibition against indiscriminate attacks or the prohibition against the use of ‘human shields’ – are derived from it. IHL also prohibits hostage-taking. There is no legal significance in describing deliberate acts of violence against civilians or civilian objects in situations of armed conflict as ‘terrorist’ because such acts already constitute serious violations of IHL.

Moreover, IHL specifically prohibits “measures” of terrorism and “acts of terrorism.” Article 33 of the Fourth Geneva Convention states that “collective penalties and likewise all measures of intimidation or of terrorism are prohibited.” Article 4 of Additional Protocol II prohibits “acts of terrorism” against persons not or no longer taking part in hostilities. The main aim of these provisions is to emphasize that neither individuals nor the civilian population may be subjected to collective punishment, which, among other things, obviously terrorizes. Additional Protocols I and II also prohibit acts aimed at spreading terror among the civilian population:

“Acts or threats of violence the primary purpose of which is to spread terror among the civilian population are prohibited” (see Article 51, paragraph 2, of Additional Protocol I; Article 13, paragraph 2, of Additional Protocol II).

These provisions do not prohibit lawful attacks on military targets, which may spread fear among civilians, but they outlaw attacks that specifically aim to terrorize civilians – for example, conducting shelling or sniping campaigns against civilians in urban areas.

As IHL applies only during armed conflict, it does not regulate terrorist acts committed in peacetime. Such acts are however subject to law, i.e. domestic and international law, in particular human rights law. Irrespective of the motives of their perpetrators, terrorist acts committed outside of armed conflict must be addressed by means of domestic or international law enforcement agencies. States can take several measures to prevent or suppress terrorist acts, such as intelligence gathering, police and judicial cooperation, extradition, criminal sanctions, financial investigations, the freezing of assets or diplomatic and economic pressure on States accused of aiding suspected terrorists.

What about the so-called ‘war on terrorism’?

This is a term that has been used to describe a range of measures and operations aimed at preventing and combating terrorist attacks. These measures include intelligence gathering, financial sanctions, and judicial cooperation; they could also involve armed conflict. The legal classification of what is often called the ‘global war on terror’ has been the subject of considerable controversy. While the term has become part of daily parlance in certain countries, there remains a need to examine, in the light of IHL, whether it is merely a rhetorical device or whether it refers to a global armed conflict in the legal sense. Based on an analysis of the available facts, the ICRC does not share the view that a global war is being waged; it takes a case-by-case approach to the legal classification of situations of violence that are referred to colloquially as part of the ‘war on terror’. Simply put, where violence reaches the threshold of armed conflict, whether international or non-international, IHL is applicable (see Question 5). Where it does not, other bodies of law come into play.

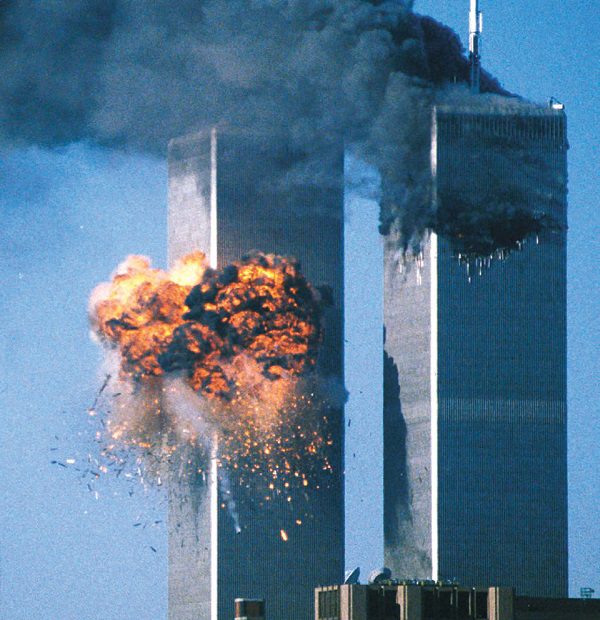

For instance, specific aspects of the fight against terrorism launched after the attacks against the United States on 11 September 2001 amount to an armed conflict as defined under IHL.

The war waged by the US-led coalition in Afghanistan that started in October 2001 is an example. The Geneva Conventions and the rules of customary international law were fully applicable to that international armed conflict, which involved the US-led coalition, on the one side, and Afghanistan, on the other. However, much of the violence taking place in other parts of the world that is usually described as ‘terrorist’ is perpetrated by loosely organized groups (networks) or individuals that, at best, share a common ideology. It is doubtful whether these groups and networks can be characterized as party to any type of armed conflict.

‘Terrorism’ is a phenomenon. Both practically and legally, war cannot be waged against a phenomenon, but only against an identifiable party to an armed conflict. For these reasons, it would be more appropriate to speak of a multifaceted ‘fight against terrorism’ rather than a ‘war on terrorism’.

What law applies to persons detained in the fight against terrorism?

1. Persons detained in connection with an international armed conflict waged as part of the fight against terrorism – the case with Afghanistan until the establishment of the new government in June 2002 – are protected by IHL applicable to international armed conflicts.

a) Captured combatants must be granted prisoner-of-war (POW) status and may be held until the end of active hostilities in that international armed conflict. POWs may not be tried merely for participating in hostilities, but they may for any war crimes they might have committed. In this case, they may be held until they have served any sentence that is imposed. If the POW status of a prisoner is in doubt, a competent tribunal must be established to rule on the issue.

b) Civilians detained for imperative reasons of security must be accorded the protection provided for in the Fourth Geneva Convention. Combatants who do not fulfil the criteria for POW status (who, for example, do not carry arms openly) or civilians who have taken a direct part in hostilities in an international armed conflict (so-called ‘unprivileged’ or ‘unlawful’ belligerents) are protected by the Fourth Geneva Convention provided they are enemy nationals. Unlike POWs, such persons may be tried under the domestic law of the detaining State for taking up arms, as well as for any criminal acts they might have committed. They may be imprisoned until they have served any sentence that is imposed. If they are not prosecuted, they must be released as soon as the imperative reasons of security that led to their internment cease to exist.

2. Persons detained in connection with a non-international armed conflict waged as part of the fight against terrorism are protected by common Article 3, Additional Protocol II when applicable and the relevant rules of customary IHL. The rules of human rights law and domestic law also apply to them. They are entitled to the fair trial guarantees of IHL and human rights law if they are tried for crimes they might have committed.

3. All persons detained outside of an armed conflict in the fight against terrorism are protected by the domestic law of the detaining State and by human rights law. They are protected by the fair trial guarantees of these bodies of law if they are tried for crimes they might have committed.

No person captured in the fight against terrorism can be considered to be outside the law. There is no such thing as a ‘black hole’ in terms of legal protection.