According to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA), there are around 81,000 Americans missing and unaccounted for from World War II, the Vietnam War, the Cold War, the Gulf Wars, and other conflicts. Today on the podcast we get a first-hand look at the US culture of honoring the dead with dignity by learning how the US military accounts for their deceased and missing servicemembers. Then we turn to an interview with one of International Committee of the Red Cross’s forensic experts to look at how militaries across the globe do this same work.

US soldiers wearing blue gloves and yellow aprons slowly walk along what is meant to simulate the scene of a battlefield during the Northern Strike training exercise at Camp Grayling in Michigan. (Dominique Bonessi/ICRC)

The wet ground is sandy. Brush, barbed wire and potentially unexploded ordnance are scattered around. (Dominique Bonessi/ICRC)

One of the soldiers finds a human remain which triggers a set of protocols to begin the actual recovery. (Dominique Bonessi/ICRC)

Remains are placed in body bags and brought to the mortuary affairs collection point which is a compact, mobile facility that can be transported around to various collection points. (Dominique Bonessi/ICRC)

Conducting tentative identifications can be as easy as locating ID cards or dog tags–often found around the servicemember’s neck with their name, date of birth, religion, and blood type. (Dominique Bonessi/ICRC)

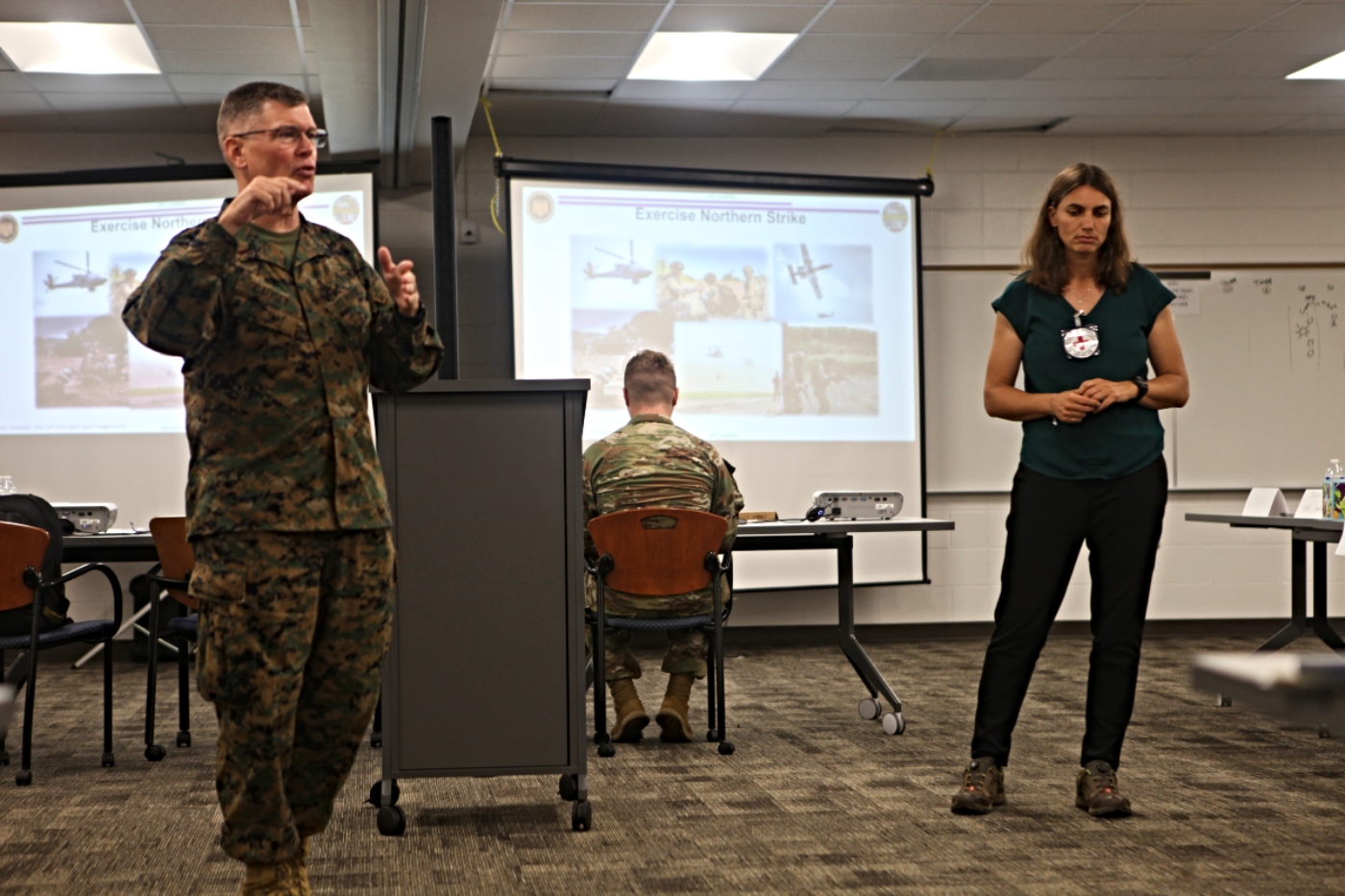

US Marine Chief Bo Causey, who prefers to go just by Bo, [on left] explains that this is the fifth year the exercise includes a mortuary affairs component to train servicemembers and test the military’s readiness. This is the first year the ICRC has been asked to participate in the working group and the observe the trainings. (Dominique Bonessi/ICRC)

Stephen Fonseca, an ICRC forensic specialist, provides his expertise to the working group. (Dominique Bonessi/ICRC)

Important Links

ICRC’s Military Personnel Identification Project

DPAA-Accounting for Missing Personnel

International Review of the Red Cross- Protection of the Dead

Arlington Cemetery Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

Transcript for the hearing impaired

[Sound of bell tolling]

[BONESSI] It’s 10am Sharp on a warm morning at Arlington Cemetery in Washington, DC.

Silence falls over the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at the changing of the guard.

[Sound of changing of the guard ceremony]

[BONESSI] The tomb is the final resting place for 3 of the US’s unidentified military personnel from as far back as World War I, meant as a memorial dedicated to all servicemembers who lost their lives in conflict and remain unidentified.

According to the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA), there are around 81,000 Americans missing and unaccounted for from World War II, the Vietnam War, the Cold War, the Gulf Wars, and other conflicts.That means their families haven’t learned about the fate and whereabouts of their loved ones since they went missing. It’s an agonizing state of limbo that loved ones must endure for years or even decades. But DPAA along with a wide array of organizations continue to work to recover, identify, and reunite fallen servicemembers with their loved ones.

Today on the podcast we get a first-hand look at the US culture of honoring the dead with dignity by learning how the US military accounts for their deceased and missing servicemembers. Then we turn to an interview with one of International Committee of the Red Cross’s forensic experts to look at how militaries across the globe do this same work. I’m Dominique Maria Bonessi and this is Intercross, conversations on conflict and the people caught in the middle of it.

[INTERCROSS INTERLUDE MUSIC]

[Sound of bus driving]

[BONESSI] I step off a bus into a hazy, humid morning at Camp Grayling in northern Michigan.

[Sound of exercise] “Move forward….Right side how are you doing? All good. Left side how are you doing?”

[BONESSI] About 10 US soldiers wearing yellow aprons and blue plastic gloves, slowly walk along what is meant to simulate the scene of a battlefield.

[Sound of exercise] “Halt…Take five steps back, going to call EOD.”

[BONESSI] The wet ground is sandy. Brush, barbed wire, and potentially unexploded ordnance are scattered around. But this is just a training exercise meant to simulate what it would be like for these soldiers to have to search for and recover the remains of one of their own. This is the first time my colleagues at the ICRC have been invited to observe and provide expertise at the US military’s annual Northern Strike training exercise. US Marine Chief Bo Causey, who prefers to go just by Bo, explains.

[BO] “ So the Northern Strike exercise is a state of Michigan joint accredited exercise where military exercise, where they bring both active duty reserve and National Guard units and members here to do, both tactical level training and operational level training.”

[BONESSI] Bo is the mortuary affairs and fatality management planner for the joint chiefs of staff at the Pentagon. On the sidelines of this exercise, Bo also runs a working group—that’s the folks you’ll hear talking in the background shortly. It’s made up of policy, technical, and logistical experts from the military’s combatant commands and other organizations around the U.S. like the ICRC.

[BO] “To talk about our requirements and our gaps and figuring out how we are going to move forward in the event that we ever had to do this job in any future military conflict.”

[BONESSI] This is the fifth year that the exercise includes a mortuary affairs component to train servicemembers and test the military’s readiness.

Back at the simulated battlefied, the ground is being checked for unexploded ordanances.

[Sound of exercise] “Alright everybody EOD has cleared us. Right side good to go?”…“Requesting K-9 assistance.”

[BONESSI] To speed up the search and cover more ground, they call in a dog trained specifically to sniff for human remains among the brush and barbed wire.

[Sound of dog barking]

[BONESSI] The dog finds two human remains and several portions of remains in a trench just a few meters away. This triggers a set of protocols to begin the actual recovery.

[Sound of exercise] “Portion one, portion two, portion 3…..11;22-11;35 is there no more blue flags.”

[BONESSI] One member of the team goes down into the trench to check for unexploded ordnances around the remains, another begins placing flags where the remains were found, while another takes notes about its’ location, condition, and other details to document the scene. The human remains are tagged with case numbers, gently lifted into body bags, and then lifted out of the trench. From there they’re brought to…

[Sound of generator]

[BO] “Mortuary affairs collections point, which is the MIRCS.”

[BONESSI] The Mobile Integrated Remains Collection System, Bo says, is a portable, self-contained facility that can be transported to different collection points. Bo says the remains are brought to this collection point to initially document the individual and obtain a tentative identification. This could be as easy as locating ID cards or dog tags–often found around the servicemember’s neck with their name, date of birth, religion, and blood type.

[BO] “And then they would go from there, they would be flown or transported to the theater mortuary evacuation point, the TMEP, which is over on the other side. That’s where they’re going now.”

[Sound of bus driving]

[BONESSI] We get back on a bus to drive to the next step in the process.

[Sound of bus]

[BONESSI] About 15 minutes later, we get off the bus at an aircraft hangar on the other side of the base. As we open the door to the simulated theater mortuary evacuation point we’re hit by the sharp smell of embalming fluid. The human remains lie on stretchers while mortician, Danielle Wilk and her team from the Air Force Mortuary Affairs Operations at Dover Air Force Base carefully embalm the human remains using a red-colored liquid, stich up any open wounds, and clean them with soap and water.

[Wilk] “When they’re done embalming, we’re going to break, and everyone’s going to part ways and we’re going to show how we lift onto the full body wrap.”

[Sound of wrapping]

[BONESSI] From there, teams of 3 to 4 people are wrapping the human remains in plastic, gauze and white fabric to ensure they can stay intact during transportation from abroad back to the continental US. US Air Force Tech Sergeant Tiffany Nicole Jenkins from Dobbins Air Reserve Base in Georgia is one of the people wrapping—what in a real scenario would be one of their fallen comrades.

[Jenkins] “When you’re in the fight you’re just go, go, go, go you’re not really processing anything and then all of the sudden everything stops, it’s quiet and you hit a brick wall. You’re never going to be the same”

[BONESSI] Sergeant Jenkins says she’s had to remind herself and younger airmen that this mission isn’t for everyone, and that mental health needs to be prioritized. That’s also why military chaplains are involved in this process.

[Martinus] “So as a chaplains, our tenants are nurture the living, cure for the wounded, and honor of the dead. That’s what we, we practice. That’s what we train for.”

[BONESSI] Chaplain Brian Martinus from the Michigan Army National Guard stands along the far wall of the theater mortuary with an example of how the human remains of a servicemember from the Jewish faith would be handled. Beyond the tactical work of ensuring bodies are treated with dignity and in the course of his 23-year military career, Colonel Martinus provided 93 families with notice of their loved one’s death. He’s also had to train notification officers to do this work.

[Martinus] “There’s no way to prep somebody to go tell somebody that they lost their loved one. It’s a lot of prayer, a lot of meditation. It’s putting, uh, things into perspective. Well, what I want from my family if I was in that situation. Every service member that we’re working with in that capacity that’s somebody’s family and that could be our family. So you want the best for your family, you’re gonna want the best for them.”

[BONESSI] If the servicemember can be transferred home, they will likely be received through Dover Air Force Base in Delaware, where the armed forces medical examiner and Air Force Mortuary Affairs Operations conduct their work. Chief Causey explains the medical examiner’s office conducts medicolegal death investigations on deceased service members who die outside the US and perform scientific identifications.

[BO] “When we’re in the field, we don’t have the current resources to do positive identification. So we’re out there to collect, uh, any identification media so that we can start the identification process. And then we’re able to upload that so it can go back to the Armed Forces Medical Examiner system for them to actually do the scientific identification so that positive ID can be obtained.”

[BONESSI] Several tools are used to do this including: fingerprints, dental scans, and sometimes DNA comparison. The Armed Forces Medical Examiner also includes a DNA identification lab, which has been crucial for identifying soldiers from current and past conflicts like those who perished at Pearl Harbor at the start of WWII.

Once a positive identification is made, the servicemember’s body is reunified with their loved ones at the mortuary affairs office. Families can meet with a chaplain, select the details for end-of-life services, and grieve.

Bo says giving families these options is a priority for the US military.

[BO] “Taking care of any of those who’ve given the, the ultimate, sacrifice and have died serving their country. The least we can do is to honor them and, you know, in a dignified and respectful manner.”

[PAUSE]

[BONESSI] We’re now going to turn to an interview with the ICRC’s Stephen Fonseca. Stephen is head of the Africa center for medicolegal systems in Pretoria, South Africa, and he is currently leading the ICRC’s Military Personnel Identification project. He attended the Northern Strike exercise over the summer and spoke with me about the project. We start with, how rules of war apply to management of the dead.

[STEPHEN] In international armed conflict, there are a number of rules that apply to the management of the dead. There’s rules around, the desecration of bodies, for instance, that’s obviously prohibited. There’s rules around the fact that all bodies need to be recovered, from the battlefield without adverse distinction.

There are, many, that apply both to the respect, dignity, and handling of bodies on the battlefield, but then that also extends to the rights of family to know the fate and whereabouts of their loved ones. Advocating for state armed forces to adhere to the Geneva conventions and international humanitarian law. What we are doing is ensuring that the primary victims, those who have died, are properly accounted for. That they don’t go missing, and that they’re hopefully identified.

[BONESSI] Going to our time in Michigan, I wanna understand that at this training that we were at with the US military, what was our role in this training?

[STEPHAN] I think there’s two parts. First, we are incredibly grateful that we are actually allowed to participate and be exposed to, exercises of this magnitude because it allows us to, to evaluate. What we are seeing, state armed forces, carry out in terms of their preparations versus what we are advocating for and providing in training and supporting capacity building in other countries.

Participating in the exercise, first of all, very selfishly for us, it’s. It’s a really great opportunity to see what is being taught, whether it’s consistent with what we’re practicing, what we’re teaching out there.

And then the flip side is, you know, we, the ICRC has over 160 years of experience working in conflict. This is where we add value because we can take different scenarios and present those as potential injects into their exercises, or it can just be a discussion or pose a question to those who are carrying out the exercises. I think being involved in these exercises, we bring all of that experience that the exposure that we’ve had in many, many different types of conflict so that can benefit those who are carrying out the exercises.

I think it’s also very important for us to reflect on how consistent. The training is in one very advanced, military compared to what we are offering. Thankfully there is a lot of consistency there, which is, very comforting.

[BONESSI] So you’ve said throughout this training that the US military seems to have this deep knowledge of forensic mortuary affairs and understanding of how to go about it. We saw a lot of deep respect. I’m curious comparing the US to other countries. What is your wider understanding of what other countries are doing?

[STEPHAN] I haven’t been to a country, and met state armed forces who haven’t impressed the importance of wanting to recover their personnel. To the best of their ability, identify them and notify families. I think that is a priority for most countries. But the reality is it’s easier said than done.

This is where the US have decades of experience that been in various counterinsurgency type environments. They’ve been in a lot of conflict where they’ve developed literally over decades. A process, a system of ensuring that people are professionally searched, recovered, evacuated, that the bodies are moved very quickly to a point where they can be properly examined by experts in the field.

They’ve also collected a lot of information such as DNA that allows for expedited identification because they’ve already got something to compare against. Where the US appeared to be very advanced is that they’ve used their experience well to come up with a system that works, generally for smaller caseloads.

I think it doesn’t matter where you are in the world, when you start dealing with large caseloads, whether it’s civilian or military, you’re always going to be challenged by your own. Capacities, the limitations of those capacities, the number of experts, the number of laboratories that can actually, process, samples.

I was just in a country in Africa recently and a very senior military, officer I met to talk about this project. He left a memorable statement. He said, we are not afraid to die. We are just afraid that we won’t be found. Soldiers know they’re going into harm’s way.

They understand the risk nobody wants to die, but they understand that there is, that there’s that, that there is that possibility but no one wants to think that their body is just going to be left out there to be scavenged, to be at the mercy of the environment, and for their family to never receive the remains back never to go through their own cultural, traditional and religious rights and ceremonies. Everybody wants to come home alive or dead. So when we are working on the project and we are dealing with countries, some that have very limited resources, some that have more resources.

It’s the same, it’s the same concern is that no one wants to be left out there. Everybody wants to come home a alive or death. And yeah, I think the US have done a very, they’ve, they, it’s very impressive what they’ve developed, but it’s also a culture, you know, families expect that their loved one is coming home that body needs to come home and the families expect nothing less. Sadly, in a number of other countries, the families don’t always expect that they’re going to get the body. They certainly hope they do, but they understand that due to lack of capacity, lack of planning, preparation, that bodies might not come home, and that bodies might be buried on the battlefield or somewhere else, and they may never actually get to mourn their loss at a grave site. So yeah, it takes a long time to build the doctrine, the systems, the processes, because it’s not one individual, it’s not one military unit. It’s a number of players that are all working in sync to ensure that eventually the body navigates through this process, quite a scientific process, and ultimately is identified and returned back to his or her family.

[BONESSI] Which brings up your project, the Military Personnel Identification Project. You’re talking with various militaries around the world about how they do this work. Can you talk about what this project is and what your goals are for it?

[STEPHAN] This is a project I am incredibly excited to be part of, and I think it fits very nicely with ICRC’s mandate of dealing with the humanitarian consequences of conflict some might think that when we talk about humanitarian consequences of conflict, they’re thinking of civilians.

And yes, we have lots of programs to try to address the affected population, the civilians, because they are often caught up in battles and conflict. But sometimes we forget that soldiers are humans. They have families, a right to dignity, respect , and respect, in my opinion, means doing absolutely everything to ensure that their body is found, identified and returned back to their families.

That, I think, is what describes respect for me. You should never give up the efforts to try and bring someone home, because that’s the one thing that all soldiers want, to come home to their families. This project really, looked at what causes soldiers to become unaccounted for in the first place.

Why do soldiers end up going missing? In conflict. And so there’s a number of different reasons, and it’s by working with over 40, state armed forces around the world. A number of consistent themes were identified as why people become unaccounted for.

Now. Some of those are sadly where. Soldiers are actually recovered. Military personnel are recovered, but they become missing in the administration process. Meaning the goal was not necessarily to identify them, but actually just to bury them, almost to get rid of the problem. Or, there’s mistakes or a lack of awareness or understanding of what it takes to get someone home and therefore families start reporting people missing.

When in fact their bodies were found and they just weren’t managed properly to the extent that they could be identified and returned. So what this project is doing, there’s four key goals. The first is we recognize, and this is for forensics. We always talking about. Closed population cases and open population cases.

Closed population cases are usually a lot easier because you kind of know who they are already. You’ve got some information that provides you a name that you can then work on towards a scientific identification. I use the example of a plane crash. If you have a plane crash, you have a manifest of who was on the plane.

So you know exactly when it happened, what time, where, and who is likely deceased. Then you can work with that small group to identify each and every one of those individuals. An open population case means that you don’t have a clue who they are. It could be a number of different incidents.

It could be many people, dying in different scenarios and none of them presenting you any sort of tentative identification that helps you direct your investigation towards information or a family that can help the identification process. What we are looking for is to, promote with the state armed forces that there are multiple, forms of identification carried by each person on the battlefield or at sea and that means a name badge on their uniform, a formal identification card, a set of dog tags on a chain so that. You know, if there’s something, heat trauma, if there’s, you know, serious scenarios where, you know, other parts, other forms of identification become lost in fire explosion, et cetera, at least the dog tags on metal and they tend to actually survive those types of impacts.

So it’s really pushing the identification, of that individual and hopefully we’ll never have to worry about using it, but as long as they have it, if. They’re in the unfortunate situation where they got, they have lost their life. At least we got a tentative, sort of purported identification that we could then pursue scientifically to make a reliable identification.

The second part of it is, we think that from the conflict projects that we’ve been part of, or that states have carried out, there’s a lot that should be taken. From military personnel before you put them in harm’s way. We almost got a captured audience here. This, these aren’t migrants where you don’t know who’s gonna be a migrant, where they’re gonna travel.

These are your own military personnel. So upon recruitment or upon deployment, this is the time for you to collect. All descriptive features anything that is unique about them, capture it by documentation and by photographs. Then collect fingerprints. Collect DNA. So we have an opportunity here to promote, to state armed forces that it’s really important, almost an insurance policy, for the deceased and their family, to collect all of this information. They likely never going to use it, and that’s great news, but it doesn’t cost a lot.

[BONESSI] Just quickly, can you mention the US’ system for collecting information from US troops?

[STEPHAN] So if we use the US example, they have certainly led the world in this regard. They have collected multiple what we call lines of evidence, they’ve collected descriptive features, a blood spot, on a card that protects the DNA for 30 years or more. They’ve collected dental features. So they’ve got an x-ray now of, the person’s dental characteristics and features. They’ve been doing this as far back as 1992.

What was explained to us is that since 1992, they do not have a single unidentified body. They have missing persons cases, but everybody that has been recovered has been identified. And part of that is because of their planning preparedness and capturing this information before putting somebody in harm’s way.

The third part is how are they actually carrying out the search and recovery to evacuate these people?

We know, through disaster victim identification in the civilian world, that this is a skilled process. This is something that you actually need to learn how to do. Is it a grid search? Is it a line search? Because you want to capture or find every little piece of everything that you are out there looking for.

It could be personal effects. It could be literally a finger, as horrible as it sounds, but that finger might be the only thing that you find of that individual that. Ultimately leads the family to know more about what happened to their loved one. So search recovery is very important. This is a field-based skillset that is learned.

And then the last part, and perhaps for us in the ICRC, one of the most important aspects is the families. The families have a role, right throughout this process, they are. Both victims, they are going through a tremendous amount of distress, having been notified of their loved one, potentially having been killed on the battlefield.

They need to be supported through this process, and it’s not just the first couple of days. There’s lots of different avenues of support that are needed. It’s financial. It’s psychosocial, emotional, medical, physical aid. Then you start dealing with administrative and, legal, support mechanisms.

For instance, if somebody goes missing and their body is not found on the battlefield, what happens to the family? Do they continue to get a salary on behalf of that individual? Are they going to be provided a death certificate? Um, do they have to go to the court and get a presumption of death order?

So this is really complicated stuff, that the families shouldn’t be left on their own to navigate. There needs to be a lot more support for families going through it. I always say to state authorities, families are your strongest advocates. They will speak highly of you when you do a great job.

And they see a process that is empathetic. That’s really shows how much the people in the system who are trying to help the family care. But if you don’t do that, they are your worst critics and become public critics really quickly, and rightfully so because you not giving them the opportunity to conduct this work.

They are left at the mercy of you and your system to ensure that their loved one comes home. So you have an obligation to do everything plus some. To make sure that you’re meeting their expectations. I’ve been doing this for 27 years and some families, have very high expectations, but guess what?

They just lost someone. It’s the worst day of their life, you are gonna have to work through good days and bad days with them. Some of their expectations are not realistic, but you know what? We don’t know what that’s like. So you’re gonna do whatever it takes to work with this family through this process.

And I think that needs to be, formalized by the state in doctrine, in standard operating procedures, et cetera. So it’s those four key elements that we are trying to promote through the project, to state armed forces.

[BONESSI] It seems like sometimes, these processes are sort of relegated to logistics. Can you go into that a little bit?

[STEPHAN] When we started the project and asked a number of, state armed forces around the world, who would be the focal point to address mortuary affairs and the management of the dead from the battlefield? It was relegated as a logistics problem.

And it’s much more than that now. I don’t want to cast those state armed forces in a bad light because technically it is a logistics problem, but it becomes a bigger problem when all of the other processes are not there. It’s a process where you’ve got different people in different places with different activities. All of them have a logistics sort of component to it. ’cause bodies need to move from the point of death on the battlefield through this complicated, almost scientific process to the point where the families ultimately receive them and you have to make sure all the way through those bodies are traceable, that they’re actually going to be handed over to the right family, that you haven’t made mistakes in terms of collecting samples and mislabeling them. So there’s a lot that requires a rigorous system to avoid misidentification I can see why it becomes a logistics problem for the state armed forces, because it’s about moving them from the battlefield back to their country of origin and then within that country to ultimately where they’re gonna be buried. From a human perspective, it is more than just shipping.

It’s emotions. It’s such an emotional role for everybody. Imagine the psychosocial support that they might need, there’s just so much more than that. And I think that’s where this project has highlighted the need for, military to have technical working groups that are comprised lawyers, forensic experts, military, police, logistics, all these different units so that they start looking at evaluating what happens and then what role do each one of them play, and what can they do to help one another more?

[BONESSI] And two to add to that list are maybe mental health counselors or therapists and, chaplains.

[STEPHAN] Yeah and, I think it was fantastic to see the chaplains, at the exercise. Not only because they were there to ensure that everybody was okay and that there was someone to talk to, even in the exercise. It can be quite an emotional exercise. It’s also important for the chaplains to understand what the personnel are going through, having to do search recovery, and evacuate remains that are sometimes in dreadful condition, very serious trauma. These are often people that knew each other. It’s very personal. That part is, extremely important. I think anybody who works in this industry , if they’re not touched by the work that they do, there would be a psychopath.

You have to feel something for the people that have lost their lives. But also having worked for many years in this business, I have to feel for the people who ultimately recover those bodies. And there’s nothing worse, in my opinion then a family member or a, or some military personnel having to recover their own. That is asking a lot. And with it comes, a lot of, psychosocial support, mental health support to make sure that people are okay. People might need support immediately, but people might need support years later. You don’t know when people need support.

This is something, that can be somewhat alleviated in by one, proper training, better exposure to what you’re going to actually be facing. I remember in one country, the people were used to recover bodies had no experience, had never had any training to do it properly, and actually caused a lot of distress at the end for these poor people.

Was not necessarily the fact that they had to recover people they knew from their own community, but that they learned later that they did it incorrectly, they had never received the training to understand how to do it properly. And at the end of it, they felt that they had really let these neighbors and these friends down by not having carried out the proper procedures.

Now, it wasn’t their fault. But there is a way of avoiding that. And that’s, from a command perspective, from a leadership perspective, this is a very difficult activity to carry out. The onus is on the leadership to make sure that those who are being asked to do it actually are professional at doing it so that they finish the process feeling proud of what they did, not embarrassed or ashamed.

[BONESSI] You have a report coming out, at some point talk about when the report is coming out and, what we can expect to see for the future of this project?

[STEPHAN] I’m happy to report, we’ve come up with some really interesting stuff and it’s been very well received. By the end of next year, we’ll have published with input from state forces, a set of global guidelines that any country can follow and implement.

And they’re really practical. This is not high level stuff. But what we also noticed that there was a need to create a military identification kit. So we came up with a sort of a prototype that we can share with state armed forces to say, Hey, here’s a fully, fully inclusive kit.

That if each soldier completed, provided samples, et cetera, you’d have a whole kit just sitting, waiting in the events that something might happen to them. And you can keep this kit for 30 years or more. So we’ve created this prototype that any state on force can now use, modify, et cetera, to get started.

’cause a lot of, the discussion was. Well, where do we start? How do we ultimately collect this information? So we are making that a lot more user friendly. We have a consultant who is helping, develop a database prototype, something that we can use, almost a business template to share with state armed forces to say. If you’re gonna collect all of this information, a lot of it is personal and private, so you are obligated to ensure that each and every one of these kits are securely stored, that they have retention periods, that there’s a number of safeguards.

We’ve also, through all of these discussions over the last year and a half, come up with a military personnel identification, evaluation, booklet. States can now evaluate themselves. It’s a quite a comprehensive book that allows ’em to go through each and every step and understand. To what extent are they prepared to deal with small numbers, larger numbers, excessive numbers, and who would be part of this process?

[BONESSI] You spent nearly a month with US military and other militaries from around the world.You’ve met several militaries around the world in your career , what is it about US culture, why is it so ingrained, this idea of no man left behind in this, in the US military? Why do you think that culture exists within the military here in the US? I’m just curious to hear your perspective on this.

[STEPHAN] I don’t know that I have the right answer, but, not being American and having to look at the system, and then compare it to many other countries, the one thing that I notice, in everyday life is, the response that public give. Military personnel in the US you know, you’ll have kids coming up and saying, thank you for your service, sir.

Or, saluting, there’s honor in it. It’s serving your country. I love the way that the Americans have, put these individuals on a pedestal because they deserve to be there. They’re literally giving up potentially everything for their country.

And I think that when it starts that way for the living, and how proud families are of their particular, family member part, their relative, being in the military. I think when that person is killed, there’s honor in that and that there’s a sacrifice that must be acknowledged. And if the bodies are left out there never recovered, never returned home. I think it’s a tremendous insult. I think there’s a huge indignity, that is demonstrated. So what I do like about the US attitude to this ultimate sacrifice is that it includes that you will do absolutely everything to show that respect, repay that favor, and make sure that somebody comes home alive or dead, and that they’re never left out there to be forgotten.

They’re always gonna be remembered. And so, yeah, I think there’s a lot for all of us to learn from that. I think it’s something that we will want to continue to promote with other armed forces around the world.

[BONESSI] That was Stephen Fonseca, an ICRC forensic expert based in Pretoria, South Africa.

If you’d like to learn more about the ICRC’s forensic work or the military identification project please visit, intercrossblog.icrc.org.

You can also follow Intercross on our Twitter handle @ICRC_DC.

See you next time on Intercross.

[OUTRO MUSIC]