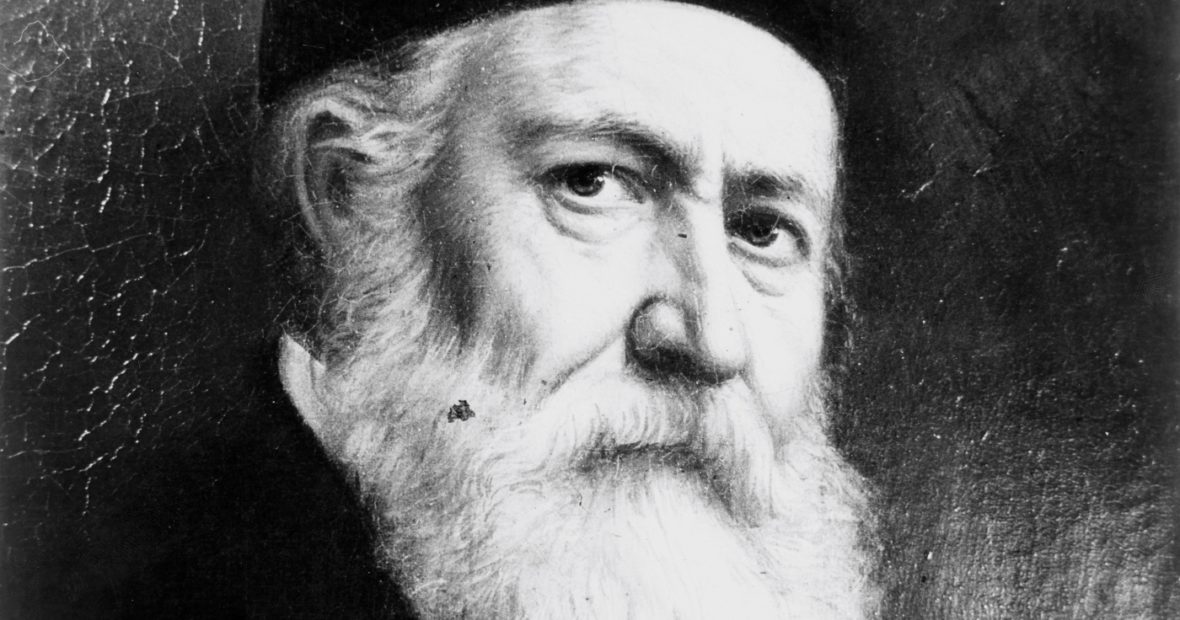

Henry Dunant is a famous historical figure, mainly known as one of the co-founders of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, initiator of the first 1864 Geneva Convention, and recipient of the first ever Peace Nobel Prize in 1901. His tumultuous life was full of paradoxes and profoundly influenced by his Christian faith.

This contribution aims to highlight this aspect of his life and showcase the hypothetical role of Dunant’s faith in the creation of the Red Cross. It synthesizes the content of a chapter recently published in a book dedicated to the fractures within Protestantism in western Switzerland during the 19th century.

Youth, faith, and Christian commitment

Born in 1828 and raised in Geneva, Henry Dunant grew up in a Christian, not to say Calvinist, family. His aunt, Sophie, took care of his religious education outside the official Genevan Protestant Church. The Dunant family was part of the so-called “Réveil” – the “Awakening” – a movement that aimed at restoring pure Protestantism. The young Dunant was deeply influenced by several local clergymen and the main principles of the Awakening faith: reading of the Bible, millennialism, proselytism and active charity – a good Christian had to be committed to charitable activities. This environment played a prominent role in forging his faith and charitable commitment.

The ideas of the Awakening manifested themselves in many of Dunant’s activities when he became a young adult. In the summer of 1847, Dunant travelled in the Alps with three friends. Inspired by this endeavour, they decided to create the “Thursday Association” (or “Thursday Readings”), a weekly gathering for young men from Geneva where they could socialize and discuss the Bible. The same year, several personalities founded a local branch of the Evangelical Alliance. Henry Dunant acted as its secretary from 1851 to 1859.

In 1844, the first Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA) was founded in London. In 1852, Henry Dunant contributed to the creation of the Geneva chapter. As “Secretary-correspondent” of the new organization, he spent much energy recruiting new members and promoting the YMCA throughout Europe. His travels and networking efforts bore fruit when he convinced the Paris chapter to organize the first YMCA World Conference in 1855. On that occasion, the delegates decided to join forces in a federation, the World Alliance of YMCAs.

These different initiatives illustrate Dunant’s evangelical commitment and active charity. Many consider him a prominent figure in the YMCA’s history. However, the sequence of events that ultimately led to the foundation of the Red Cross was not directly related to religion.

Solferino

On 24 June 1859, Henry Dunant was in northern Italy, trying to meet Emperor Napoleon the Third to discuss several questions related to the business he was running in Algeria. The same day, French and Austrian troops fought the famous battle of Solferino, one of the deadliest of the 19th century, resulting in the wounding, killing and disappearance of more than 40,000 people. Dunant did not succeed in meeting Napoleon the Third and probably arrived once the battle was over, but he did witness its dreadful consequences, including thousands of wounded and dying soldiers with no relief or medical attention. Shaken by so much horror and suffering, he spent several days in the small town of Castiglione where he helped the local population to take care of the victims of the battle.

In the months that followed, Henry Dunant remained deeply tormented by this traumatic experience. He decided to write down his feelings in a book published in 1862, A Memory of Solferino. The book contained two innovative ideas:

1) “Would it not be possible, in time of peace and quiet, to form relief societies for the purpose of having care given to the wounded in wartime by zealous, devoted and thoroughly qualified volunteers?”

2) “some international principle, sanctioned by a Convention inviolate in character, which, once agreed upon and ratified, might constitute the basis for societies for the relief of the wounded.”

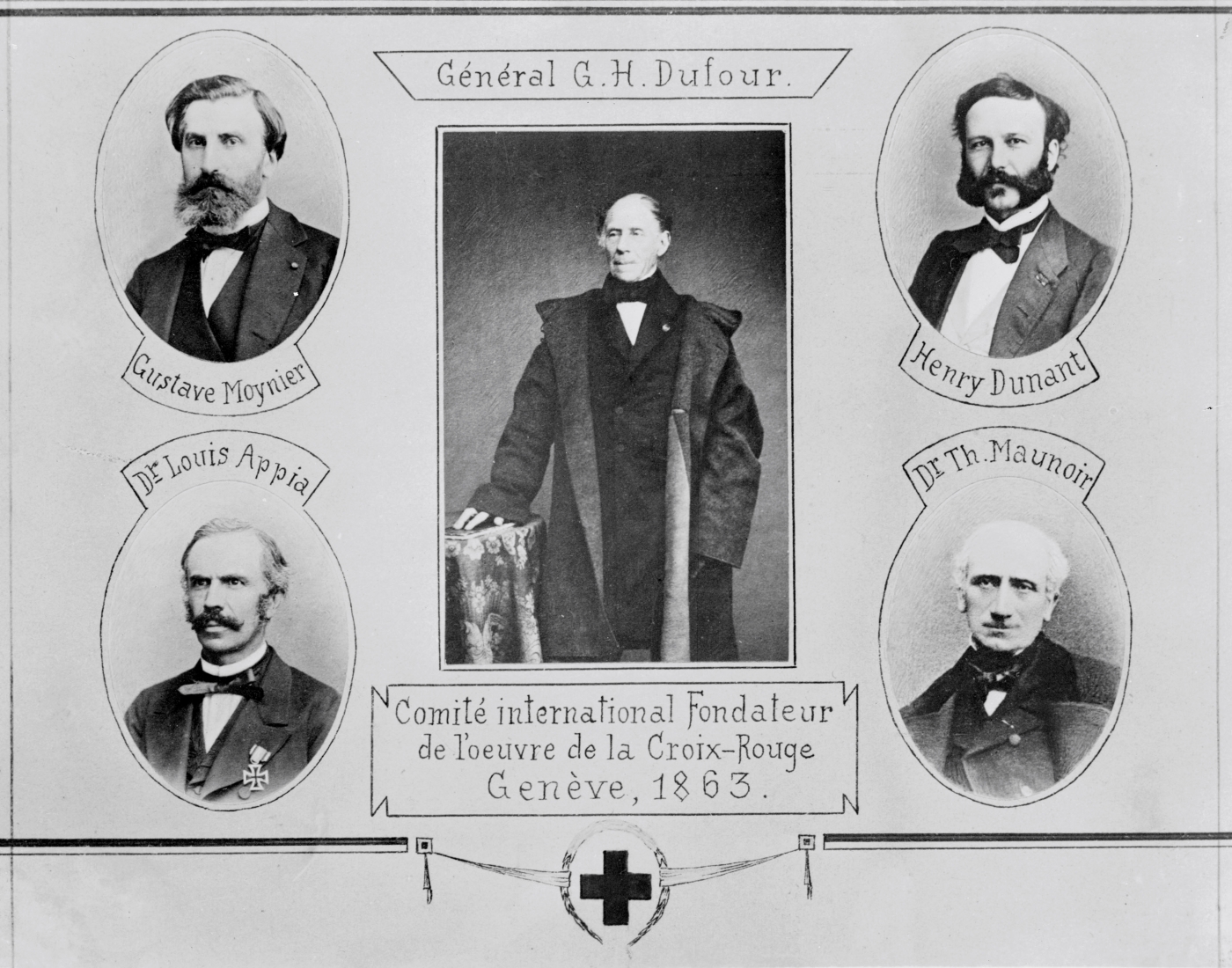

The book immediately became a huge success all over Europe, and Dunant’s proposals triggered the interest of local figures in Geneva. On 17 February 1863, under the auspices of a Genevan philanthropic society, the five founding members of the ICRC met for the first time. In October of the same year, they organized an international conference that led to the creation of the Red Cross and then also the Red Crescent Movement. A few months later, on 22 August 1864, the first Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field was signed at a diplomatic conference convened by Switzerland. Less than five years after the traumatic experience of Solferino, Dunant and the other founders of the ICRC had managed to establish what would become the most significant humanitarian movement in the world and lay down one of the first foundations of contemporary International Humanitarian Law (IHL).

The role of religious faith in the creation of the ICRC

As recalled in A Memory of Solferino, Dunant aimed to solve “a question of such immense and worldwide importance, both from the human and Christian standpoint.” The influence of his faith in the creation of the Red Cross is apparent. His commitment and efforts perfectly integrate with his vision of charitable activities influenced by the Awakening. However, did faith also influence the four other founding members of the ICRC?

Committee of Five, which founded the Red Cross : Louis Appia, Guillaume-Henri Dufour, Henry Dunant, Théodore Maunoir, Gustave Moynier

Gustave Moynier, often seen as the co-founder of the ICRC and its president for more than four decades, came from a wealthy Protestant family that was part of the Awakening. His father founded the Geneva Protestant Union, whose goal was defending against the “invasion” of Catholics in Geneva, and Moynier himself published a biography of the apostle Paul and several articles in Christian reviews. Dr. Louis Appia was a clergyman’s son also deeply influenced by the Awakening. Similarly, Dr. Théodore Maunoir was member of the Protestant Union, and General Guillaume Henri Dufour, the first ICRC president, a member of the Protestant Church.

Dunant, Moynier, Dufour, Appia and Maunoir all came from the same small conservative bourgeois elite of Geneva. Driven out of political power by local radical politics, religion was one of the few remaining refuges to preserve their values and ideological cohesion. Historians agree that faith, especially that of the Awakening, played a prominent role in the creation of the Red Cross. The founders acted as Protestant Christians, inspired by the need to live according to a sincere personal religious faith and strong commitment to charitable ideals.

However, Christianity was one of a number of factors that explain their commitment to the Red Cross project. Their social homogeneity and pre-existing social networks undoubtedly facilitated their collaboration, while the personal ambition of Dunant and Moynier in particular also partly explain the energy they dedicated to it. They both wanted to make their mark in the world. Chance, of course, also played a part, and Dunant might never have had his singular idea if he did not run a business in Algeria, or had arrived in Solferino a few days earlier or later.

Conclusion: inspired by faith, but secular in its achievement

While Christian beliefs played a role in triggering and inspiring the inception of the ICRC, the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, and the Geneva Conventions, their actual realization was nevertheless secular and non-denominational. The 1864 Geneva Convention enshrined the protection of all wounded and medical personnel, no matter their affiliation, and the concepts of impartiality and neutrality continue to define the Movement, and it may not take sides in hostilities at any time.

Nevertheless, Dunant and the other founders of the ICRC had a universalist vision and wanted the Red Cross to be as broad and all-embracing as possible, and they knew that the development and the success of the Red Cross Movement could only be achieved on a secular basis. Ultimately, it was a wise choice, and history proved they were right. The Red Cross was quickly acting in conflicts in countries that were not Christian, including those where religion was an issue. The creation of the Red Crescent at the end of the 19th century is just one example of the Movement adapting to this necessity and the being non-denominational.

This does not mean that religions have been disconnected from the development of the Movement. Since the 19th century, the ICRC has highlighted the universality of Red Cross values by exploring convergences with religious traditions, such as Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism. Personal faith undoubtedly inspired generations of ICRC staff and volunteers of Red Cross and Red Crescent national societies in their work. Nevertheless, their faith and belief remained rooted in their private spheres, and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is not active in the name of any God but in the name of humanity.

Henry Dunant was undoubtedly a committed Protestant Christian, influenced by the faith of the Awakening as well as by that of his forefathers. Religion played a prominent role in his life and fed his appetite for charitable activities. While following many failures and years of suffering, his personal faith evolved towards millennialism and mysticism, paradoxically, his greatest achievement, the revolution that transformed him into a historical figure, was secular.

—

Author:

Cédric Cotter is a researcher at the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). He worked for the ICRC in various positions at headquarters between 2009 and 2012 before joining the University of Geneva as a research associate from 2012 until 2016. He has authored around 20 publications on various issues related to the history of humanitarian action, the First World War and international humanitarian law. He holds a PhD in history from the University of Geneva.