Landmines can be a deadly and costly obstacle to humanitarian access in conflict zones, a single explosive device containing the potential not just to maim or kill an individual but to block the delivery of food or medicine to an entire population. That’s why locating mines is “a very relevant competence, very much tied to operations,” explains Erik Tollefsen, a former bomb disposal officer and the head of the ICRC’s Weapon Contamination Unit (WEC).

Thermal imaging cameras that can detect different heat signatures between an object and its surroundings have been around for years, but only recently have they dropped in price and shrunk to the size of a palm-held GoPro. That miniaturization of price and product has opened up new possibilities.

Drone equipped with thermal sensor

“Using innovative techniques to detect something,” is how geologist and ICRC consultant Martin Jebens describes a non-linear career path that has taken him from mineral exploration near the Arctic Circle to clearing a World War II minefield on Denmark’s Skallingen Peninsula and then onto testing cutting-edge landmine-hunting infra-red drones.

It was Jebens’ experience in the territorially complex 186-hectare Skallingen minefield a decade ago that informed his understanding of a ‘no one-size-fits-all’ approach to mine clearance. Thousands of mines were buried among the shifting sand dunes, drifting beaches and salt marshes. The dynamic and varied terrain demanded “a diverse kind of clearance, targeting the real needs in different areas.”

Working in a protected nature reserve also taught Jebens the importance of a less invasive approach to mine clearance, one in which the environment is left as intact as possible: the antithesis of driving a mine flail across a field and blowing stuff up.

His own experience in conflict zones led Tollefsen to a similar conclusion about the need for new, bespoke ways of doing things. “If the objective is to provide food assistance to a population, then it’s not about how many mines you clear, it’s all about getting the trucks through to feed the people,” he says, “We’re more like enablers… providing access,” he says. Not every case of weapon contamination has to become “a million-dollar demining project”.

International Collaboration

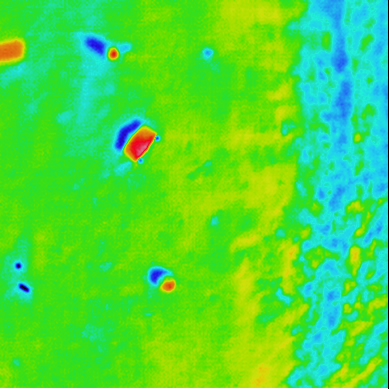

Flying at an altitude of around 10 meters or lower, the GPS-enabled thermal camera captures differential heat signals at or just below the surface of the ground and pinpoints the anomaly. Perhaps it is a landmine, warmed by the sun’s heat and cooling faster than the soil in which it lies, or perhaps it is just a piece of harmless scrap.

Thermal image captured by drone

That is where Tokyo’s Waseda University comes in, and Hideyuki Sawada, a professor of applied physics in the university’s School of Advanced Science and Engineering. Since 2018, the ICRC and Waseda have worked to expand their collaboration beyond seminars on International Humanitarian Law (IHL), explains Mamiko Tomita, Waseda Program Officer in Tokyo. While thermal imaging for landmine detection is the first joint project, new ways of partnering are a guiding principle for the ICRC’s innovation work.

“Recent AI technologies will surely contribute to the automatic recognition of different types of weapons. These techs will be applied to the thermal images”, says Sawada. Thousands of images of mines and other munitions, captured by the infrared camera, will be fed into a machine learning program to improve the speed and accuracy of identification. “We can train the machine to recognize patterns so that we improve the probability of detection, and at the same time reduce the false alarm rate,” says Tollefsen.

German Tellermine on the Danish West Coast

The team have seen positive results so far and are already thinking about the next step: manufacturing. “We can make a technology that is cheap, easily-accessible and solves a humanitarian problem,” says Tollefsen of the prototype hacked together for a few thousand dollars, so the next step will be getting a device to market.

Already discussions are underway with three Japanese companies – NEC, Terra Drone, and Sora Technology – with the aim of making an affordable product available to all humanitarian organizations who see an application, perhaps even beyond weapon contamination.

Thinking aloud, Tollefsen and Jebens enthused about the possibilities; everything from locating graves, to surveying refugee populations to determine their access to heating and cooking facilities or identifying one broken solar cell among an array of panels. “We have this new technology but are only beginning to understand how we can use it,” says Tollefsen.

- More on new technologies