The Philippines has one of the most overcrowded penitentiary systems in the world. It is also one of the countries most exposed to extreme weather events, natural disasters and the increasing impact of climate change.

For those jailed in high hazard exposure areas, it’s rough justice.

Mapping by the ICRC has found that roughly a quarter of the 130,000 detainees held in Philippine jails are in areas at high risk of one or more of the following: floods, drought, typhoons, landslides, heatwaves, earthquakes and volcanoes.

And they are not alone when it comes to the Asia Pacific region.

Detention-related solutions make up three out of the five pilots recently approved for funding and technical support under the ICRC’s Asia Climate & Conflict Challenge.

This is the latest regional Challenge to be rolled out by the ICRC’s Innovation Team, following Africa (six pilots supported) and the Near and Middle East (12 pilots supported).

“The Challenge series seeks out and supports new solutions to strengthen climate adaptation and resilience in conflict-affected areas, where the double impact of conflict and climate change can be devastating for communities,” says Innovation Team portfolio manager Mima Stojanovic.

At the heart of the focus on detention in Asia lies a new Climate Risk Mapping Approach and Tool.

Developed by the ICRC’s regional Water and Habitat (WatHab) team in Bangkok, Thailand, the solution applies climate and environmental risk screenings to detention settings. These are then compounded with a set of vulnerability and impact criteria.

Warning signs

The aim of the initiative is to identify high-risk detention facilities in four countries – Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Cambodia and the Philippines – and implement appropriate adaptation and resilience measures.

“The idea to develop this risk mapping process was triggered by the heavy floods in Cambodia in 2020 that led to the evacuation of almost 3,000 detainees from the worst-affected prisons. All in all, more than half the country’s prison population was impacted,” explains Jean-Marc Zbinden, the ICRC’s WatHab coordinator in Bangkok.

“This, along with the growing intensity of climate change, prompted us to dig deeper into the different aspects of the flooding incident and its impact on detainees. Together with the regional detention adviser, we wanted to know whether it was possible to use historic data and maps to identify areas that are more prone to different hazards.”

This led to the creation of a mapping tool that can zoom in on the different countries and regions most at risk, map the various – and sometimes overlapping – climate hazards, and then superimpose the geolocation of prisons.

“The aim is to see which are the most vulnerable from a macro perspective, based on the exposure to hazards and other criteria such as the size of the prison population, the overcrowding rate and the population type, such as women, juveniles etc.,” says Zbinden.

Risk reduction

This information can then be shared with the prison authorities and ICRC detention teams, with a view to raising awareness of the dangers and ultimately reducing the vulnerability of prisons.

“It will be important for ICRC detentions teams – consisting of protection, health and WatHab colleagues – to work closely with authorities to mitigate the identified risks and to develop contingency plans for climate-related emergencies,” says Shane Bryans, the ICRC’s regional detention adviser for Asia Pacific.

Increasing the resilience of places of detention could be achieved through measures such as:

- building flood barriers

- protecting essential services (water, electricity and sanitation)

- placing stock (medicines and food), detainee records and personal belongings on higher ground

- introducing early warning systems in conjunction with civilian authorities

- establishing contingency plans and improving staff training.

The risk mapping approach could eventually be used to influence the siting of new jails and prisons.

“We want to make these places of detention more resilient to climate-related shocks by decreasing vulnerability and increasing coping mechanisms – thereby preventing any additional harm to the detainees,” adds François Boher, WatHab head of sector for Asia Pacific.

“Climate-related shocks are highly stressful and have a massive impact on detainees in terms of wellbeing, health and protection. It’s not just an infrastructure problem. Because when you have to evacuate, it’s often at the last minute, no one’s prepared, personal belongings, medicines and files are lost or destroyed, and families have no idea where their loved ones have been taken.”

The Challenge pilot will help the Bangkok WatHab team finetune the Climate Risk Mapping Approach and Tool.

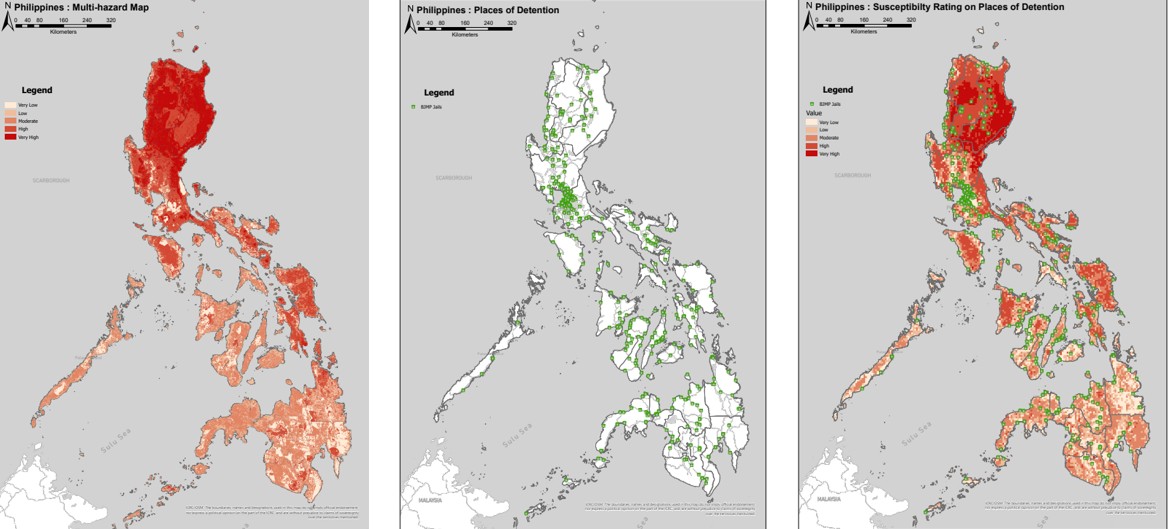

Philippines: Maps showing multi-hazard susceptibility and exposed jails. (ICRC/OSM)

Mapping is most advanced in the Philippines, which is the subject of another Challenge pilot. The Prisoners of Climate Change initiative is being led by Julien Berda, WatHab detention programme manager in the Philippines.

He has been working closely with colleagues from the ICRC’s Geographical Information Systems (GIS) Service to produce susceptibility maps of the seven main hazards in the Philippines, using official information and data.

Together, they have superimposed the hazard maps with the locations of the country’s 475 jails. These facilities, which are run by the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology (BJMP), house more than 130,000 detainees.

“Based on this exercise, we have 115 jails, with around 30,000 detainees plus BJMP staff, located in areas with a high hazard susceptibility. This shows that the lives and wellbeing of many people are at risk,” says Berda.

Scaling up

The plan is for the ICRC and the BJMP to select ten jails most exposed to the different hazards, and conduct vulnerability and capacity assessments to determine the risk level.

The next stage would be to implement risk reduction measures and then evaluate the impact. If successful, the process could eventually be scaled up to other jails in the Philippines, with the BJMP gradually taking ownership, supported by the ICRC.

In December, the ICRC delegation in Manila and the BJMP signed an MoU greenlighting the initiative and building on a long history of collaboration.

Nicole van Rooijen, the ICRC’s protection head of sector for the Asia Pacific region, says the climate risk mapping approach is gaining traction with detaining authorities across the region:

“It is a good way to engage in a meaningful manner with them and to showcase the ICRC’s relevance in making prison systems more resilient to climate change.”

Long term, the aim is to develop a climate risk mapping methodology or good practices that can then be shared across the ICRC globally.

“This hazard mapping approach could ultimately be applied anywhere in the world and to other infrastructure such as refugee camps or hospitals – or even an ICRC delegation,” says Zbinden.

The possibilities are endless.