A car bumps along a dirt road leading out of the city. Sand dunes and charcoal kilns line the road on either side. The sea can be seen over the top of the dunes. We are evacuating a young man who is in agony in the back seat of a vehicle. A pool of blood is accumulating below his foot. The car slows as it approaches a checkpoint where three militiamen carry AK-47s and a rocket-propelled grenade launcher. Warily – there have been ambushes – one of the men approaches and peers into the car.

I hold my breath for a few seconds while I watch this scene from the ICRC escort vehicle which is just behind. The driver points a finger toward the back seat and I hear him shout: “Keysaney”. Our cars are waved through without a word.

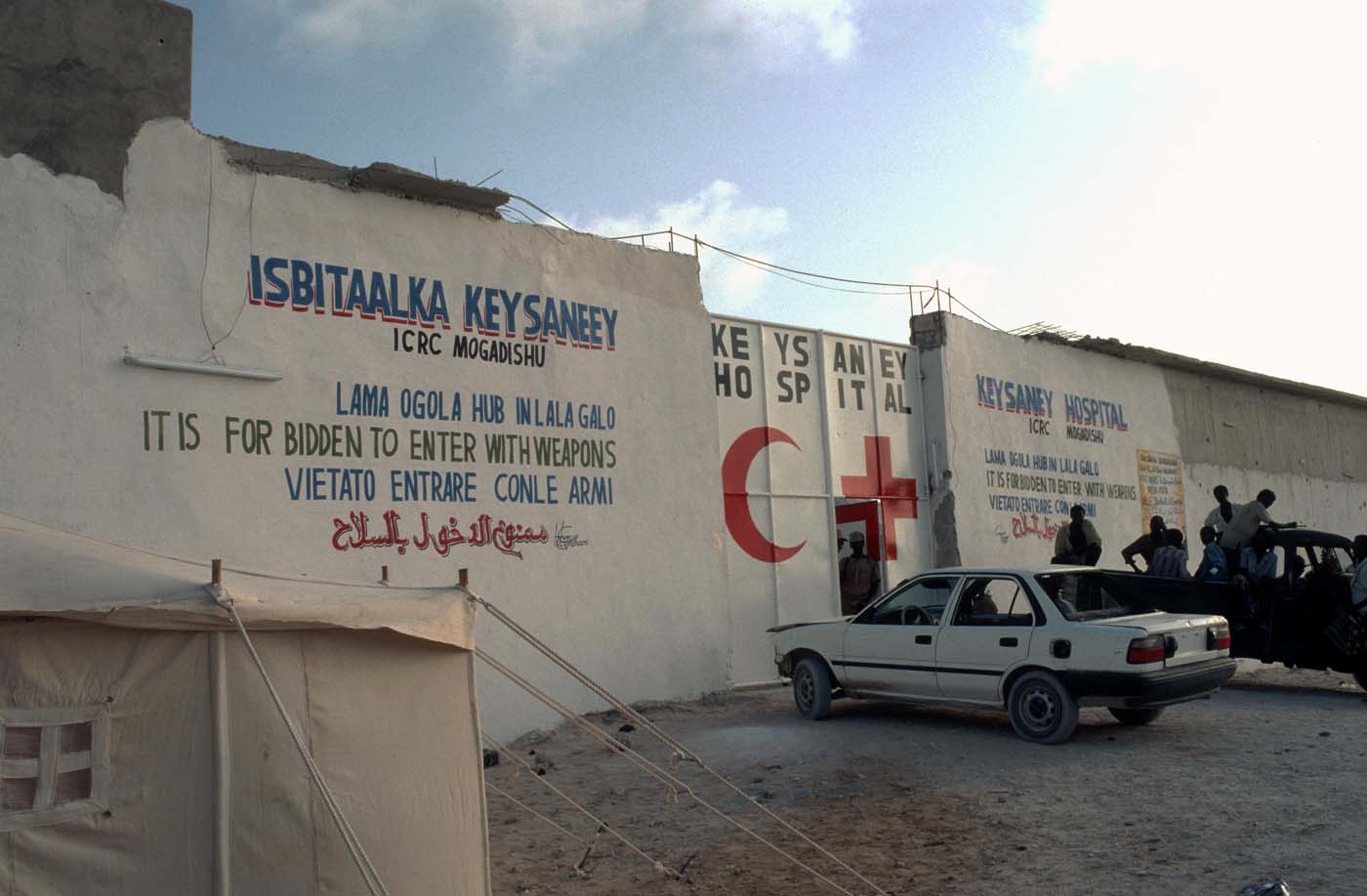

A little later, we reach high walls and come to a stop. There is a painted sign of an AK-47 with a red “X” across it: weapons prohibited. Large red letters on the white of the walls read: Keysaney Hospital.

Keysanaey Hospital entrance, 1991, marked by huge emblems of the Red Cross and the Red Crescent. ©ICRC/Robin Coupland

In late 1991, the regime of Syad Barré fell and Somalia witnessed widespread civil war. By early 1992, clan warfare had divided the capital Mogadishu into two sectors: north and south. By a coincidence of geography, all the hospitals were in the southern sector, but many doctors and nurses lived in the north.

A sign outside a Berbera surgical hospital in Somalia prohibiting weapons inside the facility. This wasn’t uncommon in the early nineties during the civil strife. Picture was taken in 1991 © ICRC/Francois de Sury

To respond to the mounting health needs, the Somali Red Crescent Society (SRCS) with the help of the ICRC planned to convert a newly-built prison into a surgical hospital just seven kilometres north of the city. There I was, helping my Somali colleagues to establish clinical and administrative protocols and training them in the techniques of war surgery and nursing. The training programmes worked well. And what we managed to set up was not just a health care facility, but a true sanctuary of humanity.

Clan warfare and extensive looting, along with a prolonged drought, caused widespread famine. Up to 500 people starved to death every day for weeks on end. The looting and fighting made Mogadishu one of the most dangerous cities in the world.

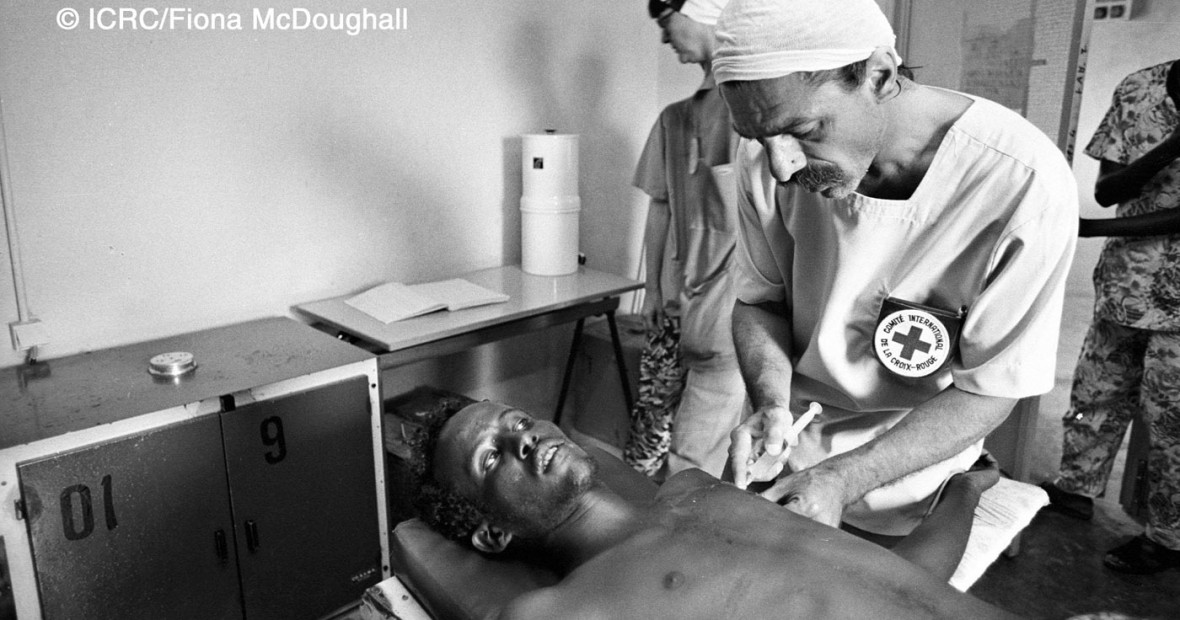

In Keysaney Hospital we were kept busy treating the wounded from the clan warfare and accompanying looting. As the looters were often targeting food, one surgeon, in a fit of dark humour, mentioned to me that he had never operated on a looter with an empty stomach.

Many times, the patients were from different clans who were fighting against each other. Yet, in the hospital all were treated solely on the basis of medical need. Families visited the wounded peacefully, while their respective militias fought it out in the streets of Mogadishu. A nurse’s eyes beamed as he told visiting ICRC medical staff “This fellow is from clan X, and this one in the next bed, is from clan Y – the same ones that are fighting in the market today.”

Years after the founding of Keysaney Hospital, the chaos continued in Mogadishu and all the hospitals in the southern part of the city closed down. For a time, Keysaney became the only surgical facility in the city, until the ICRC helped a group of doctors to restart another in the south in 2000. Nevertheless, Keysaney became famous and received patients from both parts of the city. As it was the best (and at times the only) surgical hospital in the country, patients from all over Somalia were transferred there as well.

The hospital’s neutrality was so well respected that the principle gained ground throughout Mogadishu society. This even extended to the desert road leading out of the city towards the hospital which was also considered “neutral.”

“On the way to Keysaney” people would shout from their vehicles, and the militiamen would allow them to pass without bothering to check the clan identity of the occupants. People saw this road as an extension of the hospital’s neutrality.

The SRCS hospital staff took pride in this achievement, proving that, even in the toughest conditions, the idea of a humanitarian space – a neutral hospital – could take root and flourish.

Almost twenty-five years after the founding of Keysaney, the internationally recognised government still does not control the entire country. The only national institution that has remained with universal acceptance is the Somali Red Crescent Society.

Modern day Keysaney Hospital, the Red Crescent symbol hoisted atop. The health facility is still run by the Somalia Red Crescent (SRCS) with the support of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC ) © ICRC/Pedram Yazdi