Libera nos, Domine, a bello, a fame, a peste!

On 23 May 1618, a group of Bohemian Protestants led by Count Jindřich Matyáš Thurn-Valsassina threw two Catholic governors and their secretary out of a top-floor window of Prague Castle. This episode was the unlikely flash point that set off the Thirty Years’ War. It sparked the Bohemian Revolt, which engulfed vast swathes of Europe, brought Spanish forces across the Alps to wage a campaign in the Netherlands and, rather improbably, led to the Swedish occupation of Alsace.

The 17th century was just as unpredictable, changeable and complex as the time we live in now. We can easily imagine the confusion these events caused in people’s minds, and how they overturned the established religious and moral order. The war shook up contemporary thinking, prompting an intellectual upheaval that would ultimately bring about the Enlightenment.

People have long been fascinated by the Thirty Years’ War. It is engrained in our collective memory. References to the conflict abound in literary works, from Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen’s Simplicius Simplicissimus (1668), to Bertolt Brecht’s Mother Courage and Her Children (1939) and Arturo Pérez-Reverte’s The Sun Over Breda (1998). And it continues to resonate today amid a fresh wave of religious conflict that can at times seem at odds with conventional geopolitical wisdom.

It would be impossible to cover every twist and turn of the Thirty Years’ War here. So instead, we will focus on the key developments that shaped this period in history.

The war began when Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II attempted to force Roman Catholicism on his subjects. But events gathered pace as a series of military campaigns and alliances dragged much of Europe into full-blown conflict.

It drew in major European powers of the time – the Holy Roman Empire (ruled by the Habsburg dynasty), the Catholic Church, the House of Savoy, and various German princes, as well as the national armies of Spain, Sweden, Denmark and France – alongside other forces with differing affinities. It ended in 1648 with the Peace of Westphalia – a treaty that, indirectly, laid down the principles of legal equality between States, non-intervention in internal affairs and dispute settlement. And in so doing, it paved the way for the global order that exists today.

Total war?

The Thirty Years’ War was a complex, protracted conflict between many different parties – known in modern parlance as State and non-State actors. In practice, it was a series of separate yet connected international and internal conflicts waged by regular and irregular military forces, partisan groups, private armies and conscripts. Because it had a profound, lasting impact on Europe at the time – drawing in entire sections of contemporary society both on and off the battlefield – it might rightly be described as an example of total war.

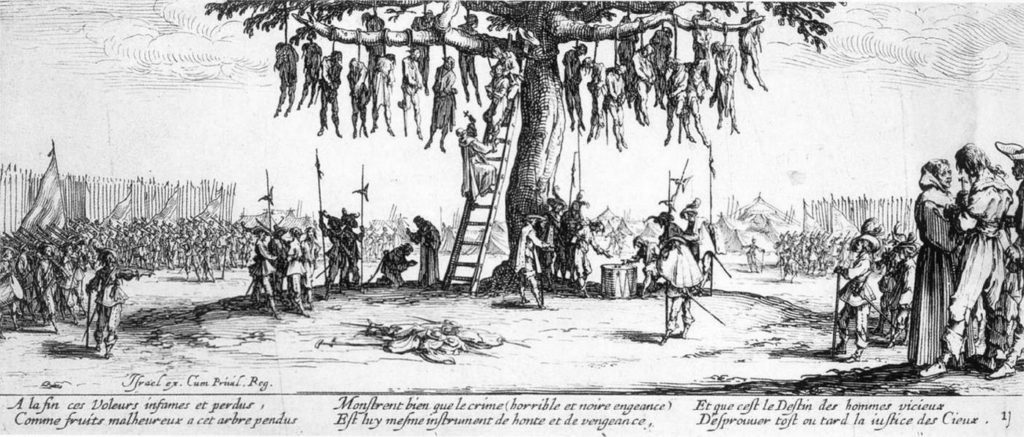

New fighting forces emerged – versatile mercenary troops and armed marauders who carried out atrocities with utter impunity. And a new breed of war profiteers came to the fore – people like Albrecht von Wallenstein who sought to maintain hostilities for personal gain and looked to turn a profit from one campaign to fund the next. In some ways, war became an industry in its own right. Profiteers plundered resources at every opportunity to sustain their business model, leaving entire regions devastated with no chance of a quick recovery.

The timeline reveals a series of campaigns and temporary truces negotiated by the Catholic Church, interspersed with unusually violent battles and ambitious raids that took troops far from their military bases and deep behind enemy lines. The widespread chaos that ensued – sieges, pitched battles, occupations and brutal repression – had a profound effect across much of Europe, and in Germany in particular.

Peasants took up arms and revolted against heavy tax burdens, occupying forces and atrocities committed by mercenary troops and vagrant soldiers – with bloody consequences. Jews were persecuted and refugees massacred in big cities such as Frankfurt and Mainz. There were mass witch trials across southern Germany. Relentless military campaigns and troop mobilization saw population displacement on a vast scale. Typhus and plague ravaged soldiers and civilians alike. And all this came against the backdrop of the “Little Ice Age”, which blighted agriculture and left food in short supply.

The cost of violence

Local authority and church records and isolated witness accounts are the only surviving evidence of how people were affected by the fighting. These sparse records suggest that direct violence against civilians was limited, but that pillaging, economic devastation and disease took a heavy human toll. Indeed, most commentators agree that many more people died from typhus and plague than from musket and cannon fire.

In 1620, the Holy Roman Empire lost around 200 men on the battlefield at White Mountain on the outskirts of Prague. By comparison, typhus – or “Hungarian fever” as it was known at the time – killed more than 14,000 imperial troops in the same year. Siege warfare also claimed countless lives, with death tolls reaching 100 people a day in Nuremberg and Breda. There were numerous plague outbreaks throughout the conflict, with cases peaking in Lorraine in 1636 during the so-called Swedish plague. As people moved in large numbers, they took disease with them and left decimated populations in their wake.

Some warlords took to funding their expeditions by bleeding entire populations dry, wreaking havoc on the economy in the process. Moreover, it was the first time that vast armies had been mobilized on this scale in Europe, and keeping so many troops well-fed far from base meant that food was at a premium.

Princes and noblemen footed the bill for troop recruitment. But fighting forces imposed local taxes, stripped assets and plundered defenceless communities to fund their own upkeep. Some armies ballooned in size, bringing in scores of civilians – chiefly family members and servants – to provide logistics support. In some cases, there were as many as four or five civilians for every combatant.

Regulating the art of war

The Thirty Years’ War saw some of the most violent and bloodiest episodes in history. But it was more than just a frenzy of wanton atrocities. From the chaos of the battlefield emerged new rules – some driven by the very pragmatic need to conserve energy, others by religious dictate.

Read more here:

The human toll

The Thirty Years’ War is thought to have claimed between 4 and 12 million lives. Around 450,000 people died in combat. Disease and famine took the lion’s share of the death toll. Estimates suggest that 20% of Europe’s people perished, with some areas seeing their population fall by as much as 60%.

These figures are remarkably high, even by 17th century standards. By comparison, the First World War – including the post-armistice outbreak of Spanish Flu – claimed 5% of Europe’s population. The only comparable example was Soviet losses during the Second World War, which amounted to 12% of the USSR’s population. The Thirty Years’ War took an immense human toll, with significant, long-lasting impacts on marriage and birth rates.

Historical sources suggest, for example, that the Swedish army alone destroyed 2,200 castles, 18,000 villages and 1,500 towns in Germany, wiping one-third of the country’s towns from the map. The 1631 Sack of Magdeburg was an unusually brutal episode. It claimed 24,000 lives – the majority burned alive in what remained of their homes. The scale of the atrocities remains a matter of some debate and we cannot say with certainty that systematic massacres took place. But the evidence shows how fighting forces used terror to repress civilians and points to pillage as common practice.

Communities agreed to pay potential invaders a Brandschatzung (fire tax) or other levy as protection money against destruction and pillage. Meanwhile, peasants sought refuge in towns and cities because it had become too risky to continue farming their land. In 1634, for example, 8,000 of the 15,000 people living in Ulm were refugees – similar, in relative terms, to the situation in Lebanon today. The price of wheat jumped six-fold in some places. By around 1648, one-third of Europe’s farmland had been abandoned or left fallow.

What can we learn from the Thirty Years’ War?

Historians broadly agree about what the Thirty Years’ War teaches us today. Some claim that it was the first example of a total war, citing its far-reaching, profound and long-lasting effects on contemporary society. To all intents and purposes it was a modern war – a mix of low-intensity conflicts and conventional battles that bore little resemblance to medieval chivalry or the 18th-century “Lace Wars”.

Some observers draw political parallels between the 17th-century wars of religion and other present-day conflicts around the world. The view, held in some quarters at least, that Westphalian sovereignty is disintegrating is fuelling creative analogies. A few years ago, for example, Zbigniew Brzezinski called the Middle East conflict a “thirty years’ war”. And when a young Tunisian street vendor set himself on fire in 2011, Richard Haas drew parallels with the Defenestration of Prague.

Some economists like Michael T. Klare claim that we could well see a return to the instability – and political and military conflict – of the mid-17th century as resources become scarcer, climate change takes its toll and national borders are redrawn. And strategists hold out hope that a Westphalia-style agreement could bring about lasting peace in some parts of the world.

Although this is an appealing political analogy, we live in a different world today. The global order, and the way the world is governed, have changed. It is always dangerous to compare two episodes so far apart in time. Similarity is no guarantee of comparability. Those who look to the past to explain modern-day events are routinely accused of having a hidden political agenda – of making things fit to suit their message.

Hybrid warfare’s devastating toll

Perhaps the most important lesson we can learn from the Thirty Years’ War lies elsewhere – in its resonance with present-day conflicts where lasting political solutions are found wanting. Documentary sources dating back more than 300 years reveal how far-reaching and long-lasting violence profoundly affected the social and political system of the day. And we cannot help but draw parallels with modern conflicts – in Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Sudan and Somalia.

In his treatise On War, Carl von Clausewitz argued for localized, quick, decisive battles to redress the balance of power. Yet the Thirty Years’ War is perhaps one of the earliest recorded examples of a protracted conflict – one where the conventional battle-and-armistice model does not apply. And in that sense, it bears many similarities with siege warfare in places such as Iraq and Syria, where both sides attempt to wear down the other but neither has the resources to win a decisive victory – with long-lasting consequences for civilians and their environment.

Economist Quintin Outram has examined the relationship between violence, hunger, death and disease during the Thirty Years’ War, arguing that the enormous humanitarian toll cannot be attributed to armed conflict or economic hardship alone.

The military battles were the catalyst for what happened during the Thirty Years’ War, but they were not the leading cause of death. The violence profoundly altered Europe’s political landscape and social fabric, and these changes were what spelled disaster on a massive scale. This process did not happen quickly. But once the violence had become endemic and self-perpetuating, change was irresistible. By contrast, the English Civil War of 1642–1651 did not have an appreciable demographic impact because the violence never reached a level that triggered economic collapse and mass displacement.

Distinguishing between concomitance, correlation and causality is an ongoing struggle for conflict theorists. Experts still disagree, for example, whether there is a causal link between malnutrition and the spread of infectious and communicable diseases. But we know for certain that widespread famine often comes as an indirect – yet no less real – consequence of warfare. A 2010 study on the war in Darfur revealed that, beyond its direct effects, armed conflict was driving other phenomena (including population displacement and restrictions on movement). The study also found that these phenomena were harming the economy, making it harder for people to sell their goods, and severely disrupting the supply chain, leaving an already-weakened local system unable to absorb future climate shocks or other major events.

In his book on the 1983–1985 famine in Sudan, Alex de Waal observed how war and violence leave people unable to fight back against worsening economic conditions. A snowball effect ensues, whereby famine and food shortages cause the social order to collapse and people lose faith in the ability of institutions – both formal and informal – to protect them. Armed violence thus weakens people’s resilience, as Mark Duffield showed when he explained how hybrid conflict gives rise to warlordism and economic predation, leaving scant hope for development.

St Vincent de Paul: the birth of humanitarian work?

In 1640, Louis XIII ordered Vincent de Paul, later canonized, to send a dozen missionaries to the duchies of Bar and Lorraine to help people suffering at the hands of the invading Swedish and occupying French forces. Contemporary records recall, in harrowing detail, what life was like – people were starving in huge numbers and the Church even received reports of cannibalism.

Read more here:

Humanitarian work in protracted conflicts

The Thirty Years’ War serves as a metaphor for the work that humanitarian organizations do in conflicts of all shapes and sizes. We have to address urgent needs. At the same time, we have to protect health and education systems, make sure people have a reliable supply of food, and keep the water running and the lights on.

Three centuries ago, people were vulnerable in many interconnected ways. The same remains true today. As humanitarians, it is our job to think about the short and the long term – to put out fires and to build fire-resistant homes. We must view conflicts not as separate events, but rather as processes that erode the very heart of our society. Every time a school is destroyed or closed down, children are deprived of an education and upbringing, leaving them at risk of joining armed groups and being unable to help rebuild their country. In this sense, war puts their future in jeopardy.

At the ICRC, we have long held this holistic view of conflict. We see emergency response and development as two sides of the same coin. We repair infrastructure, keep services running, deliver lasting improvements, nurture resilience and keep people out of poverty – all with the aim of building local capacities. We help keep the social order intact and, in so doing, avert potentially devastating and long-lasting consequences for the people we work with. Our aim, in everything we do, is to avoid the so-called perfect storm.

The Peace of Westphalia was a feat of political prowess. It brought the Thirty Years’ War to a close. And it established a new nation-state system whose principles survive to this day. But it was also the product of a worn-out, emaciated Europe. Perhaps a more fitting name would be the Peace of Exhaustion.

***

Pascal Daudin is currently Senior Policy Advisor at the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in the Policy and Humanitarian Diplomacy Division. After a short career as free-lance journalist, he joined the ICRC in 1986 and has occupied various positions of line manager, protection expert, HR policies as well as humanitarian action specialist. During this term with the organization he was deployed in major conflict situations such as Pakistan, Afghanistan, Lebanon, Iraq, Iran, Central Asia, Caucasus, Saudi Arabia and the Balkans. The ideas expressed in this blog post are the author’s own.

Congratulations to Pascal Daudin, author of this article. It is really interesting. I enyoyed very much reading this contribution. Of course I will share it with my students.

Very interesting, Pascal. I read parts of it out loud to my 15 year old which spurred a much longer conversation about what has and hasn’t changed in the world. We are happy to live in the contemporary world after all…

A refreshing read that provides important perspective. Thanks Pascal Daudin.

One step away from dishing out propaganda for Extinction Rebellion…

wow, anybody see any similarities to the current state of our world and this war? not exact but still something to think about… hopefully this doesn’t last 30 years