International humanitarian law (IHL) regulates relations between States, international organizations and other subjects of international law. It is a branch of public international law that consists of rules that, in times of armed conflict, seek – for humanitarian reasons – to protect persons who are not or are no longer directly participating in the hostilities, and to restrict means and methods of warfare.

In other words, IHL consists of international treaty or customary rules (i.e. rules emerging from State practice and followed out of a sense of obligation) that are specifically meant to resolve humanitarian issues arising directly from armed conflict, whether of an international or a non-international character.

Terminology

The terms ‘international humanitarian law’, ‘law of armed conflict’ and ‘law of war’ may be regarded as synonymous. The ICRC, international organizations, universities and States tend to favour ‘international humanitarian law’ (or ‘humanitarian law’).

Geneva and The Hague

IHL has two branches:

• the ‘law of Geneva’, which is the body of rules that protects victims of armed conflict, such as military personnel who are hors de combat and civilians who are not or are no longer directly participating in hostilities

• the ‘law of The Hague’, which is the body of rules establishing the rights and obligations of belligerents in the conduct of hostilities, and which limits means and methods of warfare.

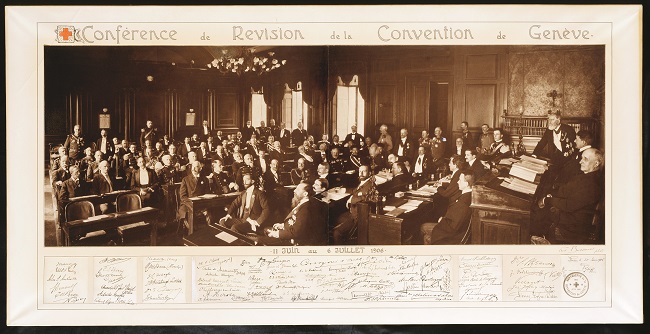

These two branches of IHL draw their names from the cities where they were initially codified. With the adoption of the Protocols of 8 June 1977 additional to the Geneva Conventions, which combine both branches, that distinction has become a matter of historical and scholarly interest.

Military necessity and humanity

IHL is a compromise between two underlying principles, of humanity and of military necessity. These two principles shape all its rules. The principle of military necessity permits only that degree and kind of force required to achieve the legitimate purpose of a conflict, i.e. the complete or partial submission of the enemy at the earliest possible moment with the minimum expenditure of life and resources. It does not, however, permit the taking of measures that would otherwise be prohibited under IHL. The principle of humanity forbids the infliction of all suffering, injury or destruction not necessary for achieving the legitimate purpose of a conflict.

“War is in no way a relationship of man with man but a relationship between States, in which individuals are enemies only by accident; not as men, nor even as citizens, but as soldiers… Since the object of war is to destroy the enemy State, it is legitimate to kill the latter’s defenders as long as they are carrying arms; but as soon as they lay them down and surrender, they cease to be enemies or agents of the enemy, and again become mere men, and it is no longer legitimate to take their lives.”

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, 1762

Essential IHL rules

The parties to a conflict must at all times distinguish between civilians and combatants in order to spare the civilian population and civilian property. Neither the civilian population as a whole nor individual civilians may be attacked. Attacks may be made solely against military objectives. Parties to a conflict do not have an unrestricted right to choose methods or means of warfare. Using weapons or methods of warfare that are indiscriminate is forbidden, as is using those that are likely to cause superfluous injury or unnecessary suffering.

It is forbidden to wound or kill an adversary who is surrendering or who can no longer take part in the fighting. People who do not or can no longer take part in the hostilities are thus entitled to respect for their lives and for their physical and mental integrity. Such people must in all circumstances be protected and treated with humanity, without any unfavourable distinction whatsoever. The wounded and the sick must be searched for, collected and cared for as soon as circumstances permit. Medical personnel and medical facilities, transports and equipment must be spared. The red cross, red crescent or red crystal on a white background is the distinctive sign indicating that such persons and objects must be respected.

Captured combatants and civilians who find themselves under the authority of an adverse party are entitled to respect for their lives, their dignity, their personal rights and their political, religious and other convictions. They must be protected against all acts of violence or reprisal. They are entitled to exchange news with their families and receive aid. Their basic judicial guarantees must be respected in any criminal proceedings against them.

The rules summarized above make up the essence of IHL. The ICRC cast them in this form with a view to facilitating the promotion of IHL. This version does not have the authority of a legal instrument and does not in any way seek to replace the treaties in force.

“Civilians and combatants remain under the protection and authority of the principles of international law derived from established custom, from the principles of humanity and from the dictates of public conscience.”

Fyodor Martens, 1899

The above, known as the Martens clause, first appeared in the preamble to the 1899 Hague Convention (II) on the laws and customs of war on land. It was inspired by and took its name from Professor Fyodor Fyodorovich Martens, the Russian delegate at the 1899 Hague Peace Conferences. The exact meaning of the Martens clause is disputed, but it is generally interpreted like this: ‘anything not explicitly prohibited by IHL is not automatically permissible’. Belligerents must always remember that their actions must be in conformity with the principles of humanity and the dictates of public conscience.