The ICRC Library’s collections retrace over 150 years of the history of the International Movement of the Red Cross and Red Crescent. Its rare books collection inherited from the ICRC founders as well as current ones offer a unique testimony to the development of humanitarian action. They also reflect the diversity of the activities of a movement working across the globe to assist victims of armed conflict and other situations of violence since 1863. These collections also include the writings of humanitarian action and law pioneers, whether they took part in the Movement’s development, inspired its action or shared its values and missions. Recently reorganized, a collection of the Library comprises the writings of these nurses, doctors, diplomats, scientists or jurists of the 19th and 20th centuries and the biographies or studies inspired by their action.

Florence Nightingale (1820 – 1910) : Portrait of a Pioneer of Modern Nursing in Writings

“Yet we are often told that a nurse needs only to be ‘devoted and obedient.’ This definition would do just as well for a porter. It might even do for a horse.”

– Florence Nightingale [1]

From Harley Street to the Crimean War battlefields

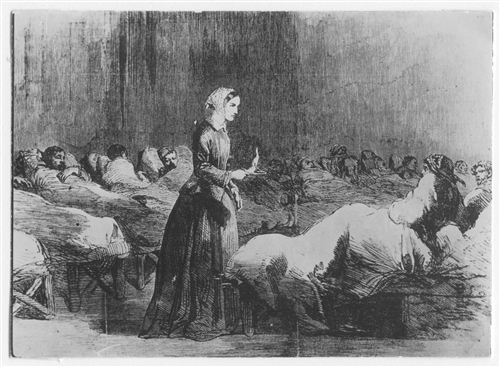

Born into a British upper class family in 1820, Florence Nightingale broke away from the social conventions of her time to embrace a career as a nurse. Dedicating her lifetime to the care of the sick and wounded, she would soon undertake to reform the entire nursing profession, at a time when hospital work was still considered a second-rate occupation for uneducated and impoverished women. Appointed by the British War Office in 1853, she lead a group of thirty-eight nurses to Scutari, near Istanbul, to tend to the wounded soldiers of the Crimean War. Like Henry Dunant in Solferino a few years later, she was struck by the shortcomings of the military medical services, underfunded and overwhelmed by the use of increasingly sophisticated and lethal firearms. The human cost of the poor sanitation and lack of appropriate care in Scutari was appalling. Overcoming the reluctance of the doctors and officers present, Florence Nightingale took upon herself to reform the military hospital, armed with her well-known leadership, sense of organization and determination. Her night time visits to her patients’ bedside, a torch in her hand, earned her the nickname of ‘The Lady with the lamp’. Sparing no effort, she would regularly write to the family members of wounded or deceased soldiers and personally answered information requests from relatives of missing fighters.

“Don’t leave it to the doctor”

After her return to England, Florence Nightingale dedicated the rest of her life to reforming hospital management, reorganizing the British military medical services and improving the education of nurses. Her visionary writings stress the importance of prevention, hygiene and professional training. Reaching an international audience, they’ve had a defining influence over the practices of countless nurses over time. Henry Dunant, the future founder of the International Committee of the Red Cross, was among her readers. Inspired by her action for wounded soldiers, he sent her a copy of his founding work. A Memory of Solferino (1864), however, failed to convince Florence Nightingale. Henry Dunant aimed to develop national rescue societies whose volunteers would tend to wounded soldiers regardless of their nationality. But Florence Nightingale was a devoted patriot, persuaded that injured combatants should be cared for by their own and that humanitarian actors ought not to take over the responsibility of the state. She also truly doubted that a convention of international law such as the one imagined by Dunant to protect the wounded and those helping them would ever be respected on the battlefield.

In her most well-known work, The art of nursing (1859), Florence Nightingale asserts with conviction the importance of her profession. Her opening chapter is quite unequivocally called Don’t leave it to the doctor. A compilation of her professional observations and recommendations also composes the volume Notes on nursing: what it is, and what it is not (1860). In addition to her writings on nursing, Florence Nightingale is known for her prolific correspondence. In 1987, a collection of her letters from her time in Crimea was published under the title ‘I have done my duty’: Florence Nightingale in the Crimean war: 1854 – 56. It comprises her detailed reports to the British War Office as well as letters conveying her instructions to the nurses working under her supervision. In A bio-bibliography of Florence Nightingale, W.J. Bishop lists her writings and presents their context of production and reception. Published in 1962, this volume remains an essential resource for those looking to get acquainted with her work.

Florence Nightingale and her biographers

The unconventional life of one of Britain’s greatest heroines has not failed to attract the attention of biographers. The numerous publications dedicated to her life and work in the first half of the 20th century have had the tendency to soften the contours of her quite imperious personality, and sometimes confuse the public declarations of a woman well versed in the art of public relations with her private opinions. I.B. O’Malley’s Florence Nightingale: 1820 – 1856: a study of her life down to the end of the Crimean War (1931) focuses on the vocation and early years of Florence Nightingale, while Irene Cooper Willis, in Florence Nightingale: a biography (1931), recounts the obstacles faced by a woman wishing to pursue a career outside of the domestic sphere in the highly conservative Victorian era. In 1950, Cecil Woodham-Smith’s classic biography, available both in English and French in the ICRC library, exploited archival materials newly uncovered. Her laudatory, well-known biography definitely contributed to turn the famous nurse into a true legend. In this context, the 1982 publication of F.B. Smith’s study Florence Nightingale: reputation and power goes thus truly against the grain. Highly critical of her achievements, the author draws a quite unflattering portrait of a woman usually perceived as a paragon of virtue and devotion as he underlines her talent for power and manipulation.

More recent publications shed light on other aspects of Florence Nightingale’s personality and action, offering a more nuanced portrait. They focus on her political career after the Crimean war and her work for the reform of the British public health system. Romanticizing biographical accounts give way to the careful examination of her theories and policies. In 1991, Monica Baly published “As Miss Nightingale said …”, a selection of excerpts from her writings organized thematically and carefully analyzed. The French translation of the volume, Florence Nightingale: à travers ses écrits, is included in the ICRC library’s collections. Juliet Piggott’s book Queen Alexandra’s Royal Army Nursing Corps retraces over a century of existence of the British Military Nursing Service and dedicates a chapter to Florence Nightingale’s key contribution during her appointment as ‘superintendant of the Female Nursing Establishment of the English General Military Hospitals in Turkey’. [2] A few years later, in the article Florence Nightingale: statistician and consultant epidemiologist, Jocelyn M. Keith sheds light on a little-known aspect of her work, her pioneering role in the use of statistics for the development of public health policies. Published in 2005 by the American Nurse Association, the volume Florence Nightingale today: healing, leadership, global action studies the legacy of the reforms undertaken by Florence Nightingale for the nursing profession.

In 2008, Mark Bostridge publishes Florence Nightingale: the making of an icon, a new biography of reference almost entirely based on recently uncovered archival materials. Far from attacking her character in the manner of F.B. Smith, Bostridge deconstructs the legend built around the figure of the Crimean war nurse to separate history from myth and better acknowledge the extent of her contribution to modern nursing. More recently, Judith Lissauer Cromwell published Florence Nightingale, feminist, a ‘post-feminist account of this modern woman’s life’ [3] that highlights her pioneering role in opening up career opportunities for Victorian women and shifting public perception of the nurse’s work. Perhaps her most admirable achievement was indeed to turn nursing, then considered a duty for which women were designed by nature, into a commendable, respectable profession in which one ought to be trained. From these studies emerges a personality no less remarkable than before, deserving of critical attention both for her crucial role in the development of nursing and public health policies and for the long-lasting trace she left in the collective imagination. Recognized as a pragmatic and obstinate administrator rather than a selfless and faultless caretaker, Florence Nightingale gains in professional recognition what she may have lost of her mythical appeal.

Florence Nightingale and the International Movement of the Red Cross

As a pioneer of medical assistance on the battlefield, she is often described as a precursor of the International Movement of the Red Cross and a source of inspiration for Henry Dunant. They certainly shared the common objective to alleviate war sufferings, with a determination triggered by the same horrifying vision of the wounded agonizing on the battlefield. But, as has often been noted, their values and approaches differed significantly. In 1973 already, Pierre Boissier dedicated an article of the International Review of the Red Cross to the similarities and differences of their respective action. Twenty years later, the review published a new portrait of The Lady with the lamp in which Isabelle Raboud notably pointed out how her correspondence with the families of her patients prefigured the ICRC’s action for restoring family links in wartime.

The volume Préludes et pionniers : les précurseurs de la Croix-Rouge 1840 – 1860 (1991) published under the direction of Roger Durand and Jacques Meurant dedicates two chapters to Florence Nightingale. In Florence Nightingale, the Common Soldier and the International Succour, Barry Smith certainly acknowledges Nightingale’s lack of sympathy for Dunant’s visionary ideas. But he also argues that their association is not entirely unwarranted. Through her dedication to the cause of wounded soldiers and her work for the reform of military sanitary services, Florence Nightingale comes to embody the values of humanism, charity and volunteerism at the heart of the International Movement of the Red Cross, even though she never abode by its principles of neutrality, impartiality and independence. The second chapter, Florence Nightingale and the Crimean War: private truth and public myth, dissects her public image. Sue Goldie Moriarty analyzes the impact of her extreme notoriety, at first orchestrated by the British Secretary of War Sidney Herbert to win public sympathy, on her action as well as on the posthumous reception of her texts and reforms.

The Florence Nightingale Medal

In her honor, the ICRC created in 1912 the Florence Nightingale Medal, as suggested by the Council of delegates during the Eighth International Conference of the Red Cross. The medal, highest international distinction for nursing professionals, is awarded every two years to outstanding collaborators of a National Society of the International Movement of the Red Cross and Red Crescent. It recognizes exceptional devotion and courage in the care of the wounded and sick as well as key contributions to the fields of prevention, public health or nursing education. Attributions of the medal are announced via an official ICRC circular, featured in this research guide. The list of the 2019 recipients can be found here. For more information, the award regulations are featured in the Handbook of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement and can be consulted online.

[1] Florence Nightingale, Notes on Nursing for the Labouring Classes, London: Harrison, 1861, p. 86

[2] Juliet Piggott, Queen Alexandra’s Royal Army Nursing Corps, London : L. Cooper, 1990, p. 13

[3] Judith Lissauer Cromwell, Florence Nightingale, feminist, London; Jefferson, NC : McFarland, 2013, p. 5

I was employed at the Veterans’ Affairs Hospital in Leeds Massachusetts from 1998 until 2018…in the engineering department and during that time also got to learn a lot about its history. The facility indirectly was opened based on Nurse Nightingale birthday (12 May). US President Warren G Harding made 12 May 1921 (and every may after it) National Hospital Day. This facility was built in 1922-1924. It was actually finished between Feb and April of 1924 but the official opening date was adjusted to 12 May 1924 in order to help ensure a public presentation (as this facility also had some legal and construction controversies…in what develop into a scandal…and that is still a curiosity). So in adjusting the date to include both Nurse Nightingale Birthday and National Hospital Day officials hoped to make the opening a more positive event. It worked! Later that week of May 12th was devoted to National Nurses week. I thought all that was interesting!